Were you aware that in the Medieval Islamic world, celebrated scientists such as Ibn Sina used to relay their teachings through poetry? Poems structure and rhythm aided the process of transmitting and memorising scientific and medical knowledge passed from teacher to student and rest of society. This article explores Ibn Sina’s (poem) Al-Urjuzah Fi Al-Tibb which consists of 1326 meticulously classified verses, and is considered as a poetic summary of his encyclopaedic textbook, "The Canon of Medicine". Its popularity was widespread in the East and later in Europe through Gerard of Cremona’s translation. As a result, it was said to be one of the most famous medical treatises in Europe, widely used in the universities of Salerno, Montpellier, Bologna and Paris up until the 17th century.

This article was originally published as: Professor Rabie E. Abdel-Halim, “The role of Ibn Sina (Avicenna)’s medical poem in the transmission of medical knowledge to medieval Europe”, Urology Annals, vol. 6, issue 1, pp 1-12, 2014. © Saudi Urological Association. To visit the original article (HTML version), click on the link. We are grateful to Professor Rabie E. Abdel-Halim for permitting republishing.

With the increased interest in literary studies and the revival of various natural sciences that occurred in the Medieval Islamic world in the 8th century, a new theme of Arabic poetry flourished with the appearance of a tradition of didactic poems composed by scholars to be used in educating and training their students. Not only were numerous medical treatises rendered into verse to help students memorise basic concepts, but essays also on other topics such as Quranic studies, Arabic grammar, history, oceanography, navigation, astronomy and even mathematics.

The Al-Urjuzah Fi Al-Tibb, or Medical Poem of Ibn Sina, known in Latin as Avicenna, (980-1037) is the most notable example of this genre and is the subject of this study evaluating its poetical and pedagogical significance. As well as, assessing its role in the transmission of medical knowledge to Medieval Europe.

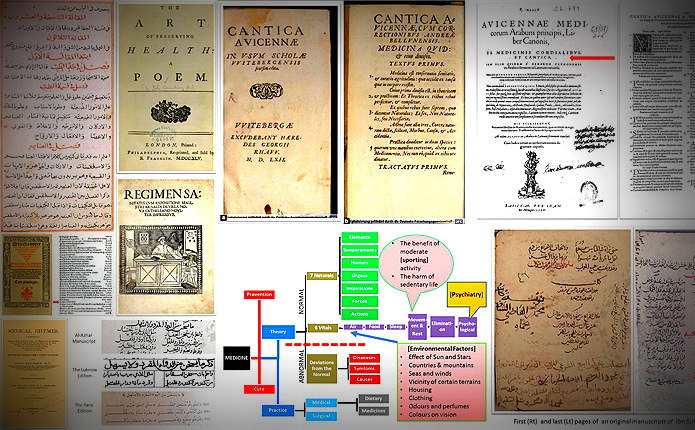

In addition to an original manuscript (Figure 1) from the Al-Azhar University’s Collection in Cairo[i], the following primary sources were also studied:

All the above-mentioned texts of Ibn Sina’s medical poem were studied and compared in order to assess the following points:

The name urjuzah given to Arabic didactic poems indicates two characteristic features. Firstly, poems in that genre are usually composed on the Rajaz metre whose pattern of syllabic repetitions produces a jingling sound that is particularly easy to remember. Secondly, contrary to the mono-rhythmic arrangement of standard poems, the rhyme of the first verse in an urjuzah is not followed in the remaining verses of the poem. However, there is a constant similar rhyming of the two hemistiches in each verse.

Ibn Sina was, himself, a talented and prolific poet. Ibn Abi Usaibia, in his celebrated “Classes of Physicians”, narrated 20 excerpts from Ibn Sina’s brilliant poetry covering different genres and following various metres. What is more, he also stated that Ibn Sina at the age of 17 authored a book on prosody titled, Mo’tassam Al-Shuara Fi Al-Arood (The Prosody Mainstay for Poets)[vii].

As documented by Qattaya, Ibn Sina composed several other medical Urjuzahs; regarding anatomy; health preservation during the four seasons; trialled medicament; and clinical evidence derived from taking the pulse and urine. Yet, his Urjuza Fi Al-Tibb, the subject of this study, remains the longest and most celebrated of them[viii].

The Lucknow, Paris and Aleppo editions, in addition to the English translation, include Ibn Sina’s preface to his poem both in prose and then in verse. The statements in the prose preface reveal that it was often the case that in Ibn Sina’s time poet physicians composed medical urjuzas and epitomes. Furthermore, his criticism of the medical profession due to the lack of ‘lecture meetings and […] discussions in hospitals and schools’ indicates that these educational measures were commonly practiced then. Ibn Sina described his poem as ‘dealing with all parts of medicine, drawn up in a very simple style, in convenient versification so that it may be easy, [and] less difficult to understand’[ix].

Next to the eloquent prose preface, Ibn Sina’s poem begins with 12 verses praising and thanking God for granting mankind the blessing of reasoning which enables our minds to learn, discover and see the unseen. The details of those 12 verses clearly show the unity of science, religious belief and spiritual knowledge in the minds of Medieval Islamic scholars.

In this section, Krueger translated verse No. 12 as: ‘preoccupying themselves with the body-granting to it the rightful mirth’.[x] However, as the word ‘body’, al-jasad, was not mentioned by Ibn Sina in this section, along with considering the meaning of the words, al-dhat and al-awkad, as well as keeping in line with the textual meaning of the preceding 9th, 10th and 11th verses, an alternative translation is hereby presented:

‘Because they were preoccupied with their inner soul, granting to it the surest of pleasures’.

Under this title in the poem, the definition of medicine was wonderfully/outstandingly expressed in just one verse (Figure 2) translated by Krueger as: “Medicine is the preservation of health and the cure of disease which arises from conscious causes which exist within the body”[xi]. In contrast with Krueger, considering the semantics of the words anhu and arad, an substituted translation is hereby presented: “Medicine is to preserve health and cure diseases arising from causes affecting the body and producing symptoms”. This newfound translation is also supported by one of the verses that followed in the section on the “Classification of Medicine” (verse No. 20) in which the same word, arad, is translated by Krueger as “symptom”[xii].

Therefore, in one single verse, Ibn Sina managed to give a comprehensive definition of medicine with the ability to include, in today’s language, the broad outlines of a medical curriculum:

This verse also resonates the prime emphasis laid on preventive medicine during the medieval Islamic era; Hifz Al Sihha, the maintainance of health is always mentioned first by the scholars of that era, prior to the treatment of illness. Henceforth, this precedence given to the preservation of health in this verse is not dictated by a rhythmic necessity as the same sequence is also stated by Ibn Sina in his encyclpedic book Al Qanun Fi Al-Tibb, “The Canon of Medicine”[xiii],[xiv]. This represents a continuation of the principal attention given to the preservation of health and prevention of disease a philosophy derived, according to Peneloppe Johnstone[xv], from the medical guidance of Prophet Muhammad. A similar definition of medicine was given by Al-Razi (865-925) around 100 years earlier, followed by later scholars such as Al-Zahrawi (930-1013) (Figure 3) and others.

The classification scheme used by Ibn Sina in the Urguza is typical of the well-documented skill in classifying, and writing down knowledge according to a plan along with rigorous orderly method. This method was conducive to an original, lucid, concise but precise and up-to-the point style, representing a salient feature of medical textbooks authored during the Islamic era. This is documented by many renowned scholars such as Charles Cumston and Lucien Leclerec, who are thought to have admired the clarity of medical textbooks written by Physicians in the Islamic world, when compared with those of ancient authors[xvi],[xvii]. This is an extension of a general trend that spread among the leading medieval scholars in Islamic civilisation from various disciplines, many of whom, as stated by Nasr[xviii] and Bakar[xix], devoted much of their intellectual energy to the subject of classification of sciences and knowledge. This trend was first demonstrated in the religious sciences, yet can clearly be seen in their studies of jurisprudence, and its source methodology, as well as in the documentation of Prophetic traditions.

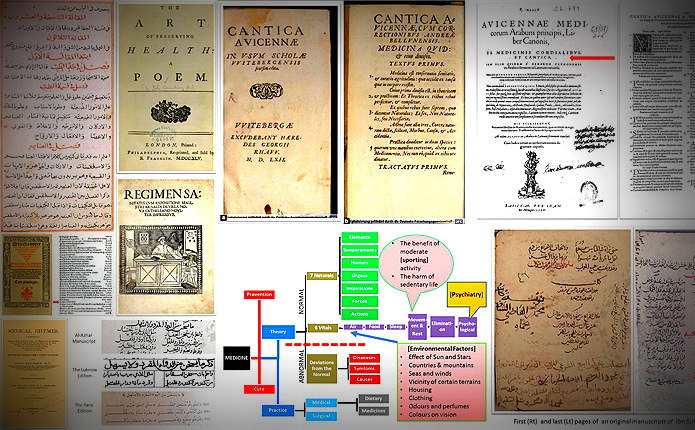

Figure 4 is a simplified schematic outline of the classification plan of the first 212 verses of Ibn Sina’s Medical poem. The poem first divided medicine into prevention and cure, followed then by theory, practice along with each division being consequently further subdivided and arborised.

The theory part includes what is known at that time about both the normal and abnormal states of the human body. In the normal states seven natural factors and six vitals are mentioned. The section on the natural factors starts with the following two verses:

“The elements are the constitutive parts of the body.

The opinion of Hippocrates on the subject is accurate; there are four of them: water fire, earth [and] air”[xx].

These verses indicate that Ibn Sina, like his predecessors in the Islamic civilisation, first reviewed the literature of scholars from ancient civilisations and therefrom adopted what they thought was correct, acknowledging the source they quoted from or agreed with.

The humoral theory developed by Hippocrates and propagated by Galen was adopted and favoured by the scholars in Islamic civilisation because it gave the most rational basis to the theory and practice of medicine available at that time.

The rest of this section continues discussing the theoretical basis of the seven natural and six vital factors that were thought, then, to lead to and control the normal state of a healthy body.

In line with his predecessor Al Razi, and conforming to the Islamic teaching of exalting the soul, the mind and the body at the same time, Ibn Sina emphasised the importance of psychological factors in the preservation and restoration of health. In this section, while discussing the natural forces, he devoted five verses under the separate title of “Psychic Forces” or “Forces of the Soul”[xxi]. Moreover, he stated another four verses in the section on the vital factors titled in the original as Al-Ahdath Al-Nafseyyah, or “Psychiatric Events”) but translated by Krueger as “Sensations”[xxii]. This was obvious, too, in the treatment section of the poem when Ibn Sina recommended good company and music in the management of convalescent persons[xxiii]. He also emphasised the role of environmental factors and highlighted the benefit of moderate sporting activity, alongsidewarning against the harm of a sedentary life[xxiv].

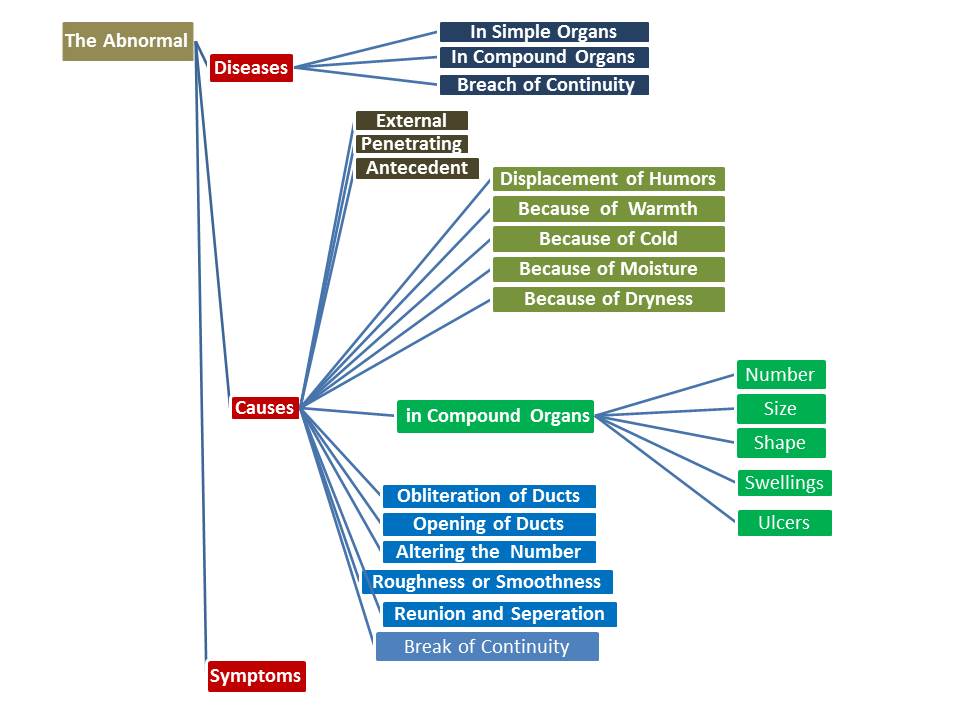

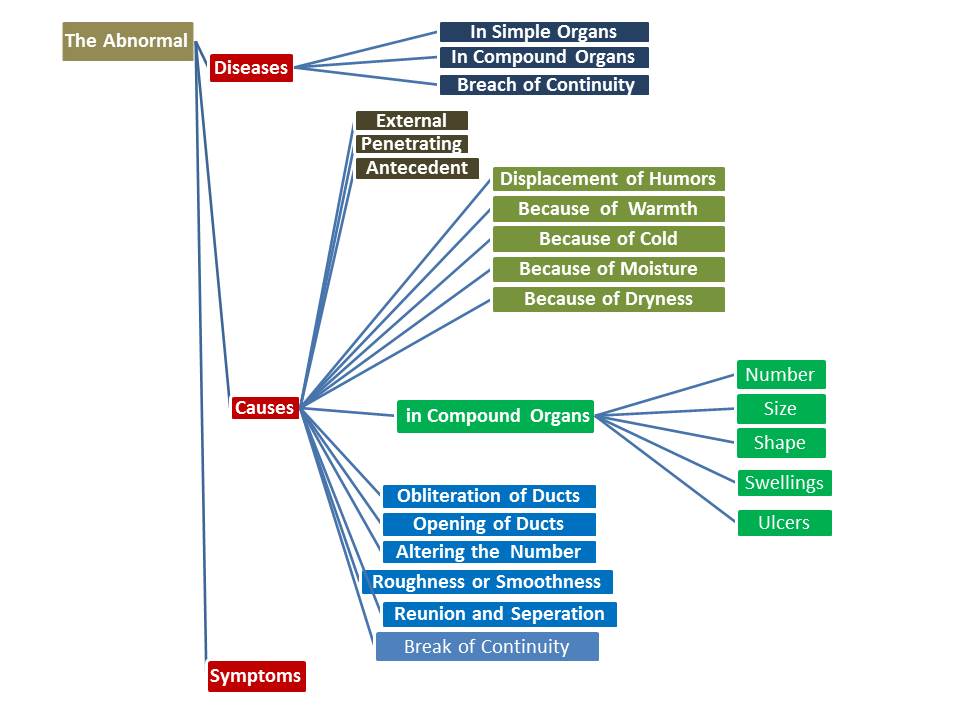

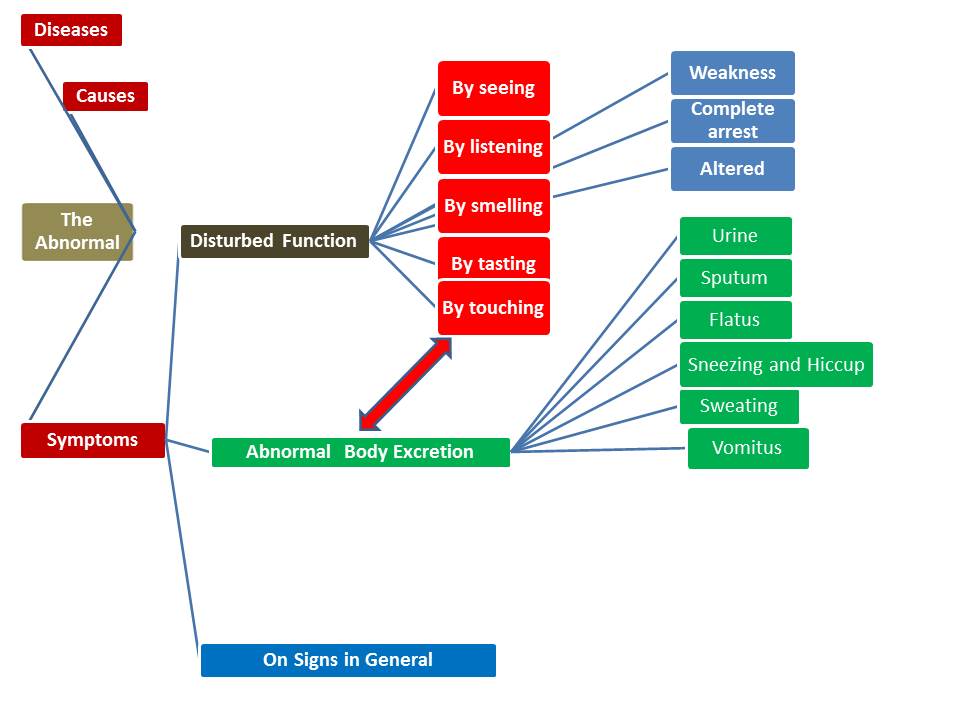

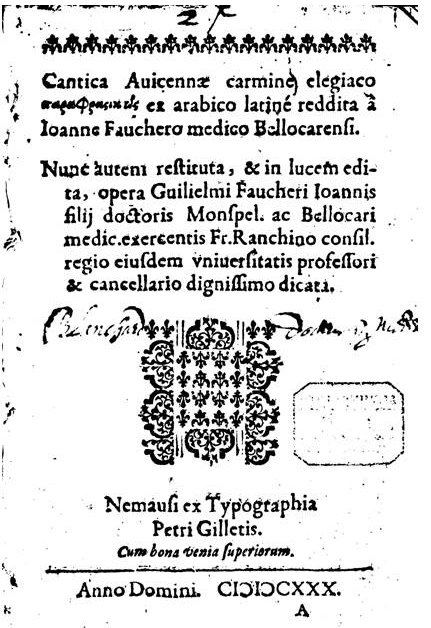

The above-mentioned section of Ibn Sina’s medical poem composed of 190 verses is equivalent to the physiology of today’s medicinal practices. Moreover, it is followed by a section on the deviations from the standard practices in which Ibn Sina versified the description of different types of diseases and their causes. This was in light of the most rational knowledge available at his time; that is to say a disturbed humoural balance (Figure 5). In a highly detailed system of classification, extending from verse No. 213 until verse 305, he described different pathological changes due to various etiological factors including congenital anomalies and birth related injuries[xxv]. The 93 verse-long section covered what we describe today as pathology and etiology. It is followed by the longest section in the poem; the section on “Symptoms”[xxvi].

As explained by Ibn Sina in lucid verses from the beginning of this long section on “Symptoms2, the aim is to detect the site of the disease causing the disturbed function responsible for the symptoms. For this purpose, contrary to the medieval practice of relying solely on observing patient’s urine samples to make a diagnosis, Ibn Sina recommended using all five senses of the doctor; examining the patient first then observing what is eliminated from their body later (Figure 6). Verses 313 to 318 of the poem as translated by Krueger reflect this well:

“Symptoms are obtained through physical examination of the body at certain moments

There are some visible ones such as jaundice and oedema

There are some perceptible to the ear such as gurgling of the abdomen in dropsy

The foul odour strikes at the sense of smell; for example that of purulent ulcers

There are some accessible to taste such as the acidity of the mouth

Touch recognizes certain ones; the firmness of cancer”.[xxvii]

It is to be noted that, in the third verse of this excerpt (verse No. 315 of the poem), Krueger used the words “gurgling of the abdomen” to translate the Arabic sentence khadkhadat al batn which in reality is interpreted as “shaking of the abdomen” in whichit is assumed the examining physician tests for the presence of free fluid and air in a viscus or cavity. The physical sign described in the aformentioned verse is what we today refer to as succussion splash test’ which has remained a part of modern clinical methods. In particular, for those clinicians who still insist on utilising their clinical sense to reach a provisional diagnosis prior to resorting to imaging techniques.

In addition, the Arabic words endal jass mentioned in the excerpt’s last verse (verse 318 of the poem) refer to the clinical method of palpation which enables the clinician to feel an underlying swelling. The use of palpation in clinical examination of patients was such a common practice in the medieval Islamic era that it was used by al-Mutanabbi, the tenth-century acclaimed poet, in a fascinating simile describing a lion walking gently and confidently in pride[xxviii] as hereby translated:

Gently stepping on the ground; out of his pride

As if it was a surgeon palpating a patient.

In this section of the poem on “Symptoms”, Ibn Sina proceeds with further discussion of the diagnostic signs related to the past and present course of the illness, as well as prognostic signs that could help in anticipating its future outcome. He also discussed the general signs that help in diagnosing disease in each of the major organs of the body such as the brain, the liver and the heart. What is more, he interlinked this knowledge with a discussion on clinico-pathological correlations to explain the arising symptoms and signs. Ibn Sina went into great detail of this revelation; allocating 54 verses to discuss the diagnostic signs obtained from examining the patient’s pulse; 21 verses for signs obtained from examining the sputum; 41 from urine; 29 from the stool; and 13 verses for signs obtained from examining perspiration. Moreover, Ibn Sina composed 264 verses to discuss at length the general and special prognostic signs that help in anticipating the course of the disease.

In total, Ibn Sina devoted 466 verses of his medical poem to the discussion of symptoms and signs of diseases. This reflects a continuation of the pioneering development made by Al-Razi in establishing clinical medicine and differential diagnosis[xxix],[xxx]. Furthermore, it is in agreement with Cumston who described the Arabian physicians as “keen observers who excelled in diagnosis and prognosis with their description of symptoms, showing a precision and originality that could be only obtained by direct study of the disease”[xxxi].

With the end of the theoretical section of the poem, the beginning of the second section is devoted to medical practice but starting, as noted before, with preventive medicine; the art of preserving health through dietary regimens, hygienic housing and a healthy environment. Among the topics discussed in this 209 verses-long section are the following[xxxii]:

In support of the previously-mentioned influence of the medical guidance of Prophet Muhammad, Ibn Sina and his predecessors give prime attention to the preservation of health as outlined in the following verses of his poem:

“If you wish to avoid illness, divide your stomach into 3 parts.

A third for respiration, a third for food and the rest for water”.[xxxiii]

Figuratively, the two verses mentioned above are versification of the last part of the following authentic Prophetic tradition:

The Messenger of God said: “The son of Adam does not fill any vessel worse than his stomach. It is sufficient for the son of Adam to eat a few mouthfuls to keep him alive. If he must fill it, then one-third for his food, one-third for his drink, and one-third for his breath”.[xxxiv]

Furthermore, in the regimen for the convalescent, Ibn Sina stated the following verses showing his care for the psychological state of the patients:

“Insist upon their quiet and rest, for their limbs are weak;

Try to lift their spirit through welcoming words and pleasant company;

Give them sweet-scented perfumes and flowers;

Obtain happiness and music for them;

Spare them sombre thoughts and fatigue”.[xxxv]

This section of the poem on the preservation of health concluded with an interesting discussion of how to manage a patient who is presented with prodromal or impending symptoms of a disease.

Subsequently followed by the second practical part, a 263 verse-long section that deals with the restoration of health for patients in use of medicine and dietary regimens is outlined[xxxvi]. After clarifying the humoral theory principle of fighting an illness with medicine, a section was then devoted to verses describing the various primary effects of different types of drugs that have the power to counteract its causing factor such as; expelling humors through stools; dominating one’s temperament; alleviating obstruction; astringents; liquidising; causing flesh to bud and so on. Long lists of simple drugs for each therapeutic effect were then given.

Ibn Sina emphasised on the need to always begin with simple drugs unless there is a reason to compliment more than one effect together. He gave practical principles for the purpose of preparing compound drugs.

Moreover, Ibn Sina discussed the degrees of strength and action of drugs, further giving examples for each. Under the title of “Simple Drugs which Warm and Do Not Purge” he began with verse No. 1043 translated by Krueger as follows:

“Beware that drugs which warm and have not been tried are”:[xxxvii]

In difference with Krueger, the more appropriate translation for that verse is:

Beware that the warming drugs are such as those which were selected and tried:

This translation is in accord with the original text in the Al-Azhar manuscript and both the Lucknow along with Paris editions (Figure 7).The verses that followed completed a list of 77 of such tried simple drugs cited in 17 verses under that title. It is remarkable that despite the long, difficult and frequently foreign names of many of those tested drugs, the poetics of the verses continued without any irregularities in the characteristic music and syllabic sequence of the poem’s metre.

Furthermore, the statement of Ibn Sina that those examples of drugs were tested is in line of what he emphasised in his Canon of Medicine:

“The potency of drugs’ nature (amzija) can be identified in two ways; one of them is analogy (qiyas) the other is by way of experimentation (tajribah). And let us start with discussing experimentation. So, we say that experimenting leads to confident knowledge of the potency of the medicine after taking into consideration certain conditions”.[xxxviii],[xxxix]

Following this 263 long section on medical treatment came the relatively shorter section on surgical treatment outlining. At first, these surgical interventions on veins and arteries included the venesection, cautery and ligation, followed by soft tissue incisions, drainage and excision. Lastly on bones, fractures and dislocations, thus giving a long list of examples in different parts of the body where excision may need to be carried out[xl]. As seen from Figure 8, this 75-verse section on surgical treatment is the remaining and shortest whilst the section on symptoms and signs is the longest. This single subdivision occupies more than one third of the poem and hence highlights the prime importance of clinical medicine to Ibn Sina.

As seen from the contents of the poem and the way it was classified, it is obvious that Ibn Sina managed to abridge the principles of medical theory along with medical practice of his time through a simple but elegant poetic style. As a result, this was a particularly helpful medium for medical education and explains the popularity alongside wide circulation of the poem both eastwards and westwards. This was manifested by the appearance of it in the Islamic world within several commentaries, and in medieval Europe within several Latin translations and prints. An interest in the poem continued in both East and West till the 17th century.

Another influence of Ibn Sina’s medical poem was the spread of popularity in composing didactic poems and utilising it in medical education. In the Islamic world, several of those medical poems written after Ibn Sina are still extant but only in the form of unedited manuscripts.

According to Sarton[xli], Latin translations of Ibn Sina’s medical poem widely existed in medieval Europe since first translated, together with his Opus Magnus, the “Canon of Medicine” by Gerard of Cremona in the 12th century. A century later, in addition to a Hebrew translation of the two books by Zarahiah Gracian and Nathan ba Meati, Armengaud de Blaise of Montpellier included a Latin translation of the Poem along with its commentary by Ibn Rushd. In 1527, Andreas Alpagus of Belluno added his efforts by producing a revision of Gerard of Cremona’s translation.

According to Krueger[xlii], the only Latin translation of Ibn Sina’s medical poem into verse was complete in the 16th century by Jean Faucher but this work was not printed until 1630. In 1649, the last prose appeared in the Latin edition by Antonius Deusingius who was the first to include an approximation of the Arabic text of the poem preface in verse.

Through the above mentioned Latin translations, the poem was celebrated in Europe during the Middle Ages. The poem was published in several 16th century printings, sometimes accompanied by a Latin translation of the commentary by Ibn Rushd (Averroes, 1125-1198). It continued to be printed and read throughout the 17th century.

The Latinised Avicenna’s poem was printed in Europe either separately as demonstrated in the editions shown in Figure 9 (a and b) and Figure 10, or combined with the translated Canon of Medicine (Figure 11) or with the Articella (Figure 12). The Articella was a famous collection of Greco Roman and Latinised Arabic medical manuscripts. They in turn were used to supply the pedagogical need for brief statements of fundamental concepts in the curricula of universities including Salerno, Montpellier and Paris up to until the 17th century. As stated by Sarton, the Latinised medical poem of Ibn Sina, known also as the Cantica Avicennae, became a perpetual part of that Articella.[xliii]

The Latinised medical poem of Ibn Sina was also the subject of several commentaries by Medieval European scholars such as the French Jacques Desparts of Tournay, Johannes Matheus Gradi, Thadea of Florence and Benedictus Rinius Venetus42.

Similarly, from the 12th century onward, Medieval Europe witnessed a rising trend of composing medical poems, particularly those related to the preservation of health. As stated by Haskins[xliv], following the flourishing of the Salerno school in the 12th century, the therapy of the Salernitan masters was popularised in the 362 lined poem, the Regimen Sanitatis Salernitanum (Figure 13). However, according to him, a more adequate statement of the early teachings of Salerno appears in various versified treaties of the 13th century Gilles de Corbeil who came from the school of Salerno and Montpellier to Paris. His medical poems became didactic classics and were widely studied, copied, and commented upon. This same trend to write medical poems continued into the eighteenth (Figure 14) and nineteenth centuries (Figure 15).

Figure 1: The first and last pages of an original manuscript of Ibn Sina’s Medical Poem (Reference No.1)

Figure 2: The verse in Ibn Sina’s poem defining ‘Medicine’ in the original Arabic (top), as translated by Krueger (middle) and by the author.

Figure 3: A page from an original manuscript of Al-Zahrawi’s Al-Tasrif showing the beginning of the first Maqala (treatise, chapter). Starting with a quotation of Al-Razi’s definition of medicine: “medicine is preserving health unto healthy individuals and returning it to the sick within the limits of human abilities”. Source: Manuscript No. 4009, courtesy of Chester Beatty Library: Dublin.

Figure 4: A simplified schematic outline of the classification of the first 212 verses of Ibn Sina’s Medical poem dealing with the normal state of the body.

Figure 5: A simplified schematic outline of the classification of the section on deviations from the normal, extending from verse No. 213 until verse 305.

Figure 6: A simplified schematic outline of the classification from a section named the “Symptoms of diseases”.

Figure 7: The title and first 3 verses of the section on ‘Simple Drugs Which Warm and Do Not Purge’ in the original manuscript and the subsequent 2 Lucknow editions.

Figure 8: A schematic table showing the distribution and total number of verses of Ibn Sina’s medical poem.

Figure 9 a and b: Title page (a) and page 8 (b) of Cantica Avicennae in Use in Wittenberg School, published in 1562, courtesy of the Bayerische Staatbiblothek (BSB) and the Munich DigitiZation Center (MDZ) of the Bavarian State Library.

Figure 10: Front page of a Latin edition of Ibn Sina’s medical poem translated into verse by Johannes Faucher in the 16th century and published by Gilletis in 1630. The original may be located at the Bavarian State Library. Courtesy of Google ebooks.

Figure 11: The title page of a Latin Edition of Ibn Sina’s “Canon of Medicine” together with two of his other works; Cardiac Medicines and the Medical Poem (the Cantica Avicennae) published in 1562. The page on the right is page 1082; the beginning of the Cantica section. Courtesy of Google ebooks.

Figure 12: The title page of the Medieval European Latin textbook: the Articella. The page on the right shows a list of the authors and titles of their enclosed works including the medical poem of Ibn Sina (Cantica Avicennae); published in 1519 by Jacobum Myt in Impressum Lugduni and contains the same material included in the 1515 edition; original from: Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine; courtesy of Internet Archive.

Figure 13: Title page from the first print edition (Venice, 1480) of the Regimen Sanitatis Salernitanum, with the commentary of Arnaldus de Villanova (the Catalan). Courtesy of The Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 14: Title page of “The Art of Preserving Health: A Poem by John Armstrong [in four books: air, diet, exercise and passions]”, published by B. Franklin (London and Philadelphia) in 1745; original from US National Library of Medicine; courtesy of Internet Archive.

Figure 15: Title page of ‘Medical Rhymes Selections Ancient and Modern’ by Hugo Erichsen, published by J H Chambers and Co, Chicago in 1884; original from Yale University, Cushing Whitney Medical Library; courtesy of Internet Archive.

[i]. Ibn Sina al-Husain Abddullah ibn Ali. Urjuza Fi Al-Tibb. Manuscript No 840/95671/Tibb. Al Azhar Al-Sharif’s Manuscript Online Collection. Available at: http://www.ahlalhdeeth.com/vb/showthread.php?t=70050 .

[ii] Ibn Sina al-Husain Abddullah ibn Ali. Al-Urjuzah Al Sinaeyyah Fi Al Masail Al Tibbeyyah. Oorgoozeh or “A Treatise on Medicine” originally written by Abu Ali Ibn Sina. Abdel-Majeed (Ed). Lucknow: 1829.

[iii]. Ibn Sina al-Husain Abddullah ibn Ali. Al Urjuzah Al Sinaeyyah. Khan, M Mostafa (Ed). Lucknow: 1845

[iv] Avicenne, Poème de la Médecine, Al-Husayn Ibn Abdullah Ibn Sina, Urguza Fi T-Tibb (Cantica Avicennae). Texte Arabe, Traduction Française, Traduction Latine du XIIIe siècle, avec Introductions, notes, et index. Etabli et présenté par Henri Jahier (Professeur à la Faculté de Médecine) et Abdul_Kader Noureddine (Professeur au Lycée Franco-Musulman). Paris: Société d’Edition “Les Belles Lettres” 1956.

[v] Krueger Haven C. Avicenna’s Poem on Medicine. Springfield. Illinois: Charles C Thomas Publishers. 1963.

[vi]. Al Baba Muhammed Zuhair. Min Muallafat Ibn Sina Al-Tibbiyyah (Some Medical Works of Ibn Sina). Aleppo: Institute of Arabic Scientific Heritage and Kuwait: The Arabic Manuscripts Institute. 1974.

[vii]. Ibn Abi-Usaybia. Uyunul-Anba Fi-Tabaqat AI-Atibaa (The sources of the knowledge of classes of doctors). Nizar Reda, editor. Beirut: Dar Maktabat al Hayat; 1965. Pp. 437-459.

[viii]. Qattaya Salman. Al-Arajeez Al Tibbeyyah (Medical Poems/ Chapter 18). In: Fi Al Turath Al-Tibbi Al-Arabi (On Arabic Medical Heritage), Qattayya Salman (Ed.). Rabat: Publications of the Islamic Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (ISECO): 2005. Chapter 18.

[ix]. Krueger, Op. Cit. (5), Preface in prose. pp. 13-14.

[x]. Krueger, Op. Cit. (5), Preface in verse, pp. 14-15

[xi] Krueger, Op. Cit. (5), On the definition of the word ‘Medicine’. p. 15

[xii] Krueger, Op. Cit. (5), On the subdivision of Medicine, p. 15.

[xiii] Ibn Sina al-Husain Abddullah ibn Ali (Avicenna). Al Qanun fi al tibb (The Canon of Medicine). Kitab No 1, Vol.1, Cairo: Bulaq; 1877. Undated Reprint by Dar Sadir, 148-187.

[xiv] Ibn Sina al-Husain Abddullah ibn Ali (Avicenna). The Canon of Medicine of Avicenna. Book One. Gruner, Oskar Cameron (Translator), New York: AMS Press; 1973; pp 358-459.

[xv] Johnstone, Penelope. Translator’s Introduction. In: Ibn Qayyim Al-Jawziyya. Medicine of the Prophet, Penelope Johnstone, Translator, Cambridge: The Islamic Texts Society; 1989, reprinted twice 2001/2004. p. xxiii-xxxii.

[xvi] Cumston CG. Islamic Medicine. In: Cumston CG, editor. An introduction to the history of medicine from the time of the pharaohs to the end of the XVIII century. London (UK):

Kegan Paul, Trench, Trumbner and Co. Ltd. New York: Alfred A. Knopf; 1926. p. 191.

[xvii] Lucien Leclerc, Histoire de la médecine arabe ; Paris: Ernest Ledaux; 1876. I: p. 91-92.

[xviii] Nasr SH. Forward. In: Classification of knowledge in Islam. Bakar O (Editor). Cambridge: Islamic Texts Society; 1989, Reprinted 2012, p xi-xv.

[xix] Bakar O. Tawhid: the source of scientific spirit. In: History and philosophy of Islamic science. Bakar O. Cambridge: Islamic Text Society. First Edition 1999. Reprinted 2012. P. 2-4.

[xx]Krueger, Op. Cit. (5), On the natural components and first about the Elements, p 15.

[xxi] Krueger, Op. Cit. (5), On the properties of the soul, pp 20-21.

[xxii] Krueger, Op. Cit. (5), Sensations. pp. 25-26

[xxiii] Krueger, Op. Cit. (5), Directions for the convalescent. pp. 61-62.

[xxiv] Krueger, Op. Cit. (5), Movement and Rest. pp. 24-25.

[xxv] Krueger, Op. Cit. (5), On things which deviate from the normal state. pp. 26-31.

[xxvi] Krueger, Op. Cit. (5), The section on symptoms. pp. 31-53.

[xxvii] Krueger, Op. Cit. (5), On the varieties of symptoms obtained from the state of body. p. 31.

[xxviii] Al-Mutanabbi Ahmed Al-Husain. Diwan Abi El-Tayyib Al-Mutanabbi (Abu E-Tayyib Al Mutanabbi’s Anthology). Abdel-Wahhab Azzam (Editor).Cairo; Lajnat Al-Nashr Wa Al-Tarjamah Wa Al Taa‘lif (Committee for Publishing, Translation and Authoring), Undated (editor’s introduction dated 1944), p, 134.

[xxix] Abdel-Halim Rabie E. Pediatric urology 1000 years ago. In: Progress in Pediatric Surgery. P.P Rickham (Ed.). Berlin Heidelberg: Springer Verlag, Vol. 20, 1986: pp. 256-264.

[xxx] Abdel-Halim Rabie E. Clinical methods and team work: 1000 years ago. Letter to the Editor, The American Journal of Surgery 191 (2006) 289–290.

[xxxi] Cumston CG. Islamic Medicine. In: Cumston CG, editor. An introduction to the history of medicine from the time of the pharaohs to the end of the XVIII century. London (UK): Kegan Paul, Trench, Trumbner and Co. Ltd. New York (NW): Alfred A. Knopf; 1926. p. 192.

[xxxii]Krueger, Op. Cit. (5), On the conservation of health through diets and regimens, pp. 53-63.

[xxxiii]Krueger, Op. Cit. (5), On the beverage, p. 56.

[xxxiv] Prophet Muhammad’s Sayings (Hadith): Sunan Ibn Majah (Darussalam Edition with an English translation by Nasiruddin Al-Khattab): Kitabul Atteima (Chapters on Food): Chapter 50: Hadith 3349.

[xxxv] Krueger, Op. Cit. (5), Directions for the convalescent, pp. 61-62.

[xxxvi] Krueger, Op. Cit. (5), To return health to patients with medicines and dietary regimens, pp. 63-77.

[xxxvii] Krueger, Op. Cit. (5), On simple drugs which warm and do not purge. p. 66.

[xxxviii] Translated from: Ibn Sina (Avicenna) Kitab Al-Qanum Fi Al-Tibb (The Canon of Medicine), The second Maqalah, first Jumalah, the second Kitab, Vol.1.Cairo: Bulaq; 1877. undated Reprint by Dar Sadir, p. 224.

[xxxix] Abdel-Halim RE, Experimental Medicine 1000 Years Ago. Urology Annals. 2011 May; 3 (2): 55-61.

[xl] Krueger, Op. Cit. (5), Surgical Practice, pp. 77-81.

[xli] Sarton G. Introduction to the History of Science. Carnejie Institution of Washington. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins Company; 1927-1931. Reprinted: New York: Robert E. Krieger Publishing Co, Inc; 1975. Vol. II, Part II; pp. 790-832.

[xlii] Krueger, Op. Cit. (5), History of the poem on medicine. pp. 9-10.

[xliii] Sarton G. Introduction to the History of Science. Carnejie Institution of Washington. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins Company; 1927-1931. Reprinted: New York: Robert E. Krieger Publishing Co, Inc; 1975. Vol. I. p. 611. Footnote.

[xliv] Haskins Charles H. The twelfth century renaissance. Harvard University Press. Eighth edition, 1971. pp. 322-323.

4.7 / 5. Votes 168

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

Muslim Heritage:

Send us your e-mail address to be informed about our work.

This Website MuslimHeritage.com is owned by FSTC Ltd and managed by the Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilisation, UK (FSTCUK), a British charity number 1158509.

© Copyright FSTC Ltd 2002-2020. All Rights Reserved.