This primary-source study of four medical works of the 13th century Muslim scholar Ibn al-Nafis confirmed that his Kitab al-Mûjaz fi al-Tibb was authored as an independent book. It was meant as a handbook for medical students and practitioners not as an epitome of Kitab al-Qanun of Ibn Sina as thought by recent historians. Ibn al-Nafis' huge medical encyclopedia Al-Shamil represents a wave of intense scientific activity that spread among the scholars of Cairo and Damascus in the 13th century. Like his predecessors in the Islamic Era, Ibn al-Nafis critically appraised the views of scholars before him in the light of his own experimentation and direct observations. Accordingly, we find in his books the first description of the coronary vessels and the true concept of the blood supply of the heart as well as the correct description of the pulmonary circulation and the beginnings of the proper understanding of the systemic circulation. Those discoveries, spreading from East to West, were translated into Latin by Andreas Alpagus and appeared in the works of European scholars from Servetus to Harvey. Furthermore, this study documented several other contributions of Ibn al-Nafis to the progress of human functional anatomy and to advances in medical and surgical practice.

Professor Rabie E. Abdel-Halim*

Table of contents

1. Summary

4. The art of writing a medical textbook

5. Critical appraisal of literature and reliance on observation and experimentation

7. Contributions to the progress of urology

8. Supplement: Commentary and Response

8.1. [Ibn] Al-Nafis and Servetus by Giles N. Cattermole

8.2. Reply from the Author Rabie E. Abdel-Halim

***

Note of the editor

This article was published in Saudi Medical Journal 2008; Vol. 29 (1): 13-22 (electronic version here), followed by a “Commentary and Response” (2008 : Vol. 29 (9) : 1359-1360). It is online on the website of Professor Abdel-Halim here. The article is published on www.MuslimHeritage.com in a revised and re-edited format approved by the author. We thank Professor Abdel-Halim for allowing its republication.

***

1. Summary

This primary-source study of four medical works of the 13th-century Muslim scholar Ibn al-Nafis confirmed that his Kitab al-Mûjaz fi al-Tibb was authored as an independent book. It was meant to be a handbook for medical students and practitioners and not as an epitome of Kitab al-Qanun of Ibn Sina as thought by recent historians. His huge medical encyclopedia Al-Shamil represents a wave of intense scientific activity that spread among the scholars of Cairo and Damascus following the massive destruction of books by Hulago’s army during the devastation of Baghdad in 1258. Like his predecessors in the Islamic era, Ibn al-Nafis critically appraised the views of scholars before him in the light of his own experimentation and direct observations. Accordingly, in his books Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun, Risalat al-A’dhâ’ and Al-Risalah al-Kamiliyah, we find the first description of the coronary vessels and the true concept of the blood supply of the heart as well as the correct description of the pulmonary circulation and the beginnings of the proper understanding of the systemic circulation.

Those discoveries of Ibn al-Nafis, translated into Latin by Andreas Alpagus in a book that was printed in Venice in 1547, appeared six years later, in the Christianismi Restituto of Servetus and, in 1555, in the De Fabrica Humani Corporis of Vesalius (2nd edition) then in the works of Valvarde (1554), Columbus (1559), Cesalpino (1571), and finally Harvey in 1628. Furthermore, this study documented several other contributions of Ibn al-Nafis to the progress of human functional anatomy and to advances in medical and surgical practice.

Many historians recorded that in the 12th and 13th centuries Damascus and Cairo took the place of Baghdad as leading centers for science and culture [1]. Despite the turmoil caused by the invading Crusader and Mogul armies, great medical schools continued to advance medical knowledge and nurture medical education in those two cities and other cities of the Muslim World. Ibn al-Nafis was one of the distinguished medical scholars who lived during that turbulent era. This study is to evaluate his contributions to the progress of medicine.

Ibn al-Nafis was the 13th-century Muslim physician ‘Alâ’ al-Dîn abu al-Hasan ‘Ali ibn abi al-Hazm al-Qarshi, born in the year 1210 at Al-Qarsh near Damascus. He studied medicine in Damascus under the supervision of the distinguished professor Muhadhab al-Din al-Dakhwar in the Al-Nuri hospital’s medical school. Ibn al-Nafis moved to Cairo where he practiced and taught medicine in the Al-Naseri hospital built by Salah al-Din al-Ayyubi. Then in 1285, he became the chief physician of the Mansuri hospital, a position he held until he died in 1288 at the age of 80. Figure 1 shows the timeline of Ibn al-Nafis in relation to some of his predecessors and contemporaries who, like him, pioneered the original contributions of the Islamic school of medicine. According to Al-Dhahaby [2], Al-Sobky [3], Ibn Tagra Bardi Al-Atabki [4], al-Maqrizi [5], Al-Yafi’ [6], Sarton [7], Ziedan and Abdel-Qader [8], Ziedan [9], and many other historians [10], Ibn al-Nafis was a great physician and a prolific author, the best among his contemporaries and the most distinguished scholar of his time in the medical profession. Ibn al-Nafis was also a distinguished authority on Quranic studies, Prophetic Tradition, Islamic jurisprudence, Islamic philosophy and Arabic language studies [11]. He wrote famous authoritative works in almost each of those sciences.

Figure 1: Timeline (in CE) of Ibn al-Nafis in relation to some of his contemporaries and predecessors. The filled-in event box is for Ibn al-Nafis, the dotted-boundary box for his professor Muhadhdhab al-Din al-Dakhwar and the dashed-boundary box for Ibn al-Quff, one of his most famous students.

In order to evaluate the contributions of Ibn al-Nafis to the progress of medicine and urology, authentic primary sources were utilized to review his biography and the original Arabic editions of his book Al-Mûjaz fi al-Tibb [12] (An epitome of Medicine) together with chapters from his other medical books: Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun [13] (A commentary on the Anatomy of the Canon of Medicine [of Ibn Sina]), Risalat al-A’dhâ’ [14] (A Monograph on Physiology) and Sharh Fusul Abuqrat [15] (Commentary on the Aphorisms of Hippocrates), were studied. Furthermore, pertinent references including books, periodicals and online history-of-medicine resources have been reviewed.

4. The art of writing a medical textbook

Al-Mûjaz [16] book shows the skill of Ibn al-Nafis in classifying his medical knowledge and writing it down using a planned, rigorous and orderly method and a lucid, concise but precise and to-the-point style (Figure 2 and Table 1):

Table 1 – The general arrangement of topics in Kitab al-Mûjaz fi al-Tibb of Ibn al-Nafis.

Section I: General Principles

Subsection 1: Of the theory of medicine

Part 1: The normal

Part 2: The abnormal

Part 3: Etiology

Part 4: Symptoms and signs

Subsection 2: Of the practice of medicine

1. The science of maintaining health

2. The science of treating illness

Section II: Medicaments & Diet

Subsection 1: Simple drugs

1. Generalities

2. Mentioning of the simple drugs alphabetically listed

Subsection 2: Compound drugs

1. On the rules for compounding drugs

2. Some examples of compound drugs

Section III: Diseases of organs (and systems)

Diseases of organs, one by one starting from the brain downwards describing the causes, diagnosis and treatment

Section IV: Diseases not specific for a particular organ

Chapter 1: Fevers

Chapter 2: Crisis and lysis

Chapter 3: Swellings, ulcers, leprosy, and the plague and how to avoid it

Chapter 4: Fractures, Contusions, Dislocations, Falls and Abrasions

Chapter 5: Care of skin, hair and figure (body weight)

Chapter 6: On poisons and their avoidance

Figure 2: Chart showing the subject classification of Kitab al-Mûjaz fi al-Tibb of Ibn al-Nafis.

This represents a salient feature of medical textbooks authored during the Islamic period and is in agreement with Cumston [17] and Leclerc [18] who admired the clarity of medical textbooks written by Islamic physicians when compared with those of ancient authors. In the early biographies of Ibn al-Nafis [19], the title of this book is given as Kitab al-Mujaz fi al-Tibb (The Epitome in Medicine) or is shortened as Kitab al-Mujaz (The Epitome). None of those early biographers mentioned that the book was a summary of Kitab al-Qanun fi al-Tibb written by Ibn Sina 250 years previously.

However, almost all the recent biographers, following Hajji Khalifah [20] (1017-1067 H/1609-1657) identified the book as Kitab Mujaz al-Qanun (An epitome of the Canon book) [21]. Most of them repeated a statement that in Al-Mujaz Ibn al-Nafis meant to give a summary of Ibn Sina’s book The Canon of Medicine [22]. This is not proven by our study, which confirmed that Kitab al-Mujaz was authored by Ibn al-Nafis as an independent book intended to be a handbook of general medicine for medical students and practitioners. In his introduction to the book [23], Ibn al-Nafis did not mention The Canon of Ibn Sina at all or any plan to summarize it. Furthermore, both the arrangement and content of the chapters are different in both books.

Moreover, contrary to Iskander [24], and for the same reasons, the Mujaz of Ibn al-Nafis is not a summary of his other book Kitab Sharh al-Qanun. The most voluminous book of Ibn al-Nafis is his encyclopedic work entitled Kitab al-Sahmil fi al-Sina’a al-Tibbiya (The comprehensive book on the art of medicine) [25]. According to the 13th to 14th century historian Al-Dhahaby (1274-1348) [26], judging from its pre-planned table of contents, the book was intended to be in 300 volumes. However, Ibn al-Nafis lived only to write 80 volumes out of which, until now, only 28 volumes could be found and which are being edited and published in a series by Ziedan [27]. Al-Shamil is the sixth encyclopedic scientific work ever written by a single author. The five famous encyclopedic medical works that preceded Al-Shamil are shown in Table 2. They were all written in the period from the 9th to the 13th centuries. According to Ziedan [28], the encyclopedic work Kitab al-Shamil of Ibn al-Nafis represents a wave of intense scientific activity that spread among the scholars of Cairo and Damascus, following the massive loss and destruction of books during the devastation of Baghdad by Hulago’s army in 1258. Ibn al-Nafis was then fifty years old and at the peak of his medical experience. He wrote Al-Shamil and other scholars wrote similar huge encyclopedic works in different branches of science in an attempt to cope with the disaster and to preserve the scientific and cultural heritage pioneered by Baghdad, the leading centre of Islamic civilization in that era.

This intensive encyclopedia writing activity also extended to the Islamic scholars of the 14th and 15th centuries enriching and preserving the world’s heritage of knowledge [29].

Table 2 – Encyclopedic medical works that preceeded Al-Shamil book of Ibn al-Nafis

| Scholar | Century (CE) | Encyclopedic Book |

| Al-Razi (Rhazes) | 9-10th | Al-Hawi* |

| Ali ibn al-Abbas | 9-10th | Kamil al-Sina’a* |

| Al-Zahrawi (Albucasis) | 10-11th | Al-Tasrif* |

| Ibn Sina (Avicenna) | 10-11th | Al-Qanun* |

| Ibn Zuhr (Avenzoar) Ibn Rushd (Averroes) |

11-12th | Al-Taysir together with Al-Kulliyat** |

| Al-Baghdadi, Muhadhdhab Al-Din |

12-13th | Al-Mukhtar fi al-Tibb* |

| Ibn al-Nafis | 13th | Al-Shamil fi al-Sina’a al-Tibbiyya* |

*Written by a single author

** The first multi-authored medical textbook [30]

Table 3 – Titles and description of some of the medical works of Ibn al-Nafis

| The Book | Description |

| Al-Shamel fi al-Sina’a al-Tibbiya (The Comprehensive Book on the Art of Medicine) |

Massive encyclopedia |

| Al-Mujaz fi al-Tibb (The Epitome in Medicine) |

Comprehensive summary |

| Sharh al-Qanun (Commentary on the Canon of Medicine) |

General Principles Pharmacy |

| Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun (Commentary on the Anatomy of the Canon of Medicine) |

Anatomy |

| Risalat Al A’dha’ (A Treatise on Physiology) |

Physiology |

| Al-Muhadhab fi al-Kuhl al-Mujarrab (The Refined Book on Ophtalmology) |

Textbook on ophthalmology |

Examining Table 3, which lists of some of the medical works authored by Ibn al-Nafis, will further reveal his skill in preplanning his works. All the books integrate and complement each other. Al-Shamil [31] is an encyclopedic data base for the researcher; Al-Mujaz [32] is a handbook for medical students and the general practitioner. Anatomic, physiological or surgical details are not included in that book. Surgical details are available in volume 42 of Al-Shamil [33]; physiological in Kitab Risalat al-A’dha’ [34] and anatomical in Kitab Sharh Tashreeh al-Qanun [35]. Kitab al-Mujaz [36] contains general practice knowledge on diseases of the eye but Al-Muhadhab fi al-Kuhl al-Mujarab [37] is a book for the specialist ophthalmologist.

5. Critical appraisal of literature and reliance on observation and experimentation

Like his predecessors in the Islamic medical tradition, Ibn al-Nafis critically appraised the views of those who came before him in the light of his own experience, experimentation and direct observations. The following translation from his introduction to his book Sharh Fusul Abuqrat (Commentary on the Aphorisms of Hippocrates) clearly shows his aim of rejecting what is superfluous and accepting only what is proved to be true:

“In our previous commentaries on this book, copies (editions) varied according to the various purposes of those who requested them. However, in this copy (edition) we are going to follow what we believe is appropriate for commentary works and just right in composing and bringing together. Furthermore, with regard to throwing light on and standing by true opinions as well as denouncing those which are false and wiping out their traces; that was the constant policy we followed in all studied subjects. And may Allah guide and help us to do that [38].”

This critical appraisal is also quite obvious in his other book Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun, where he disagreed with several of the Galenic and Hippocratic doctrines. In this book, Ibn al-Nafis stated the following:

“However, as regards the function of organs, we rely only on what is dictated by investigative observations and accurate research; not caring whether it conformed with, or differed from, the opinions of those who came before us [39].”

Accordingly, in Sharh Tashrih Al-Qanun, we find one of the great discoveries in the history of physiology: the first correct description of the pulmonary circulation (translated as follows from page 293-294):

“In the human heart and in the hearts of similar beings possessing a lung, it is necessary to have another cavity where the blood becomes thin and ready to be admixed with air. Indeed, if air gets mixed with blood while it is still thick, the resulting mix will not be of homogeneous particles. That cavity is the right cavity of the two cavities of the heart. And when the blood in that cavity becomes thin, it must pass to the left cavity where the vital spirit (ruh or pneuma) is formed. But, there is no connecting passage in between them (the two cavities) because the heart substance there is compact without any obvious passage, as thought by some, or invisible passage that could transmit that blood as thought by Galen. Indeed the texture of the heart, there, is compact and its substance is thick. Therefore that blood when becomes thin, must pass through the arterial vein (pulmonary artery) to the lungs to spread in its substance and mix with air in order to purify (filter, clear) the thinnest part of it then pass to the venous artery (pulmonary vein) to be carried to the left cavity of the two cavities of the heart admixed with air and, thus, made ready to generate the vital spirit. And the blood that remains less thinner will be used by the lung for obtaining its nutrients. It is for that reason that the arterial vein was made of greater compactness and with two layers so that what passes through its pores would be very thin while the venous artery was made thin walled with only one layer in order to easily allow in what comes out of that vein. For that reason, perceptible connecting passages were made between these two vessels [40].”

In agreement with Poynter [41], Isakander [42], Castiglioni [43], and others [44], in this unambiguous description of the pulmonary circulation, Ibn al-Nafis firmly denied the Galenic concept of the existence of invisible pores in the septum between the right and left ventricles of the heart. Furthermore, the last sentence of the above-mentioned new extended translation furnishes evidence that Ibn al-Nafis discovered the capillary circulation that connects the pulmonary artery branches to the tributaries of the pulmonary vein in the lung substance. The following translated quotations from Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun show some more places where Ibn al-Nafis, using his own anatomical observations, disproved other Galenic doctrines, which were taken for granted for several hundred years:

“As regard his statement [the statement of Galen accepted by Ibn Sina] that the heart has three ventricles: this cannot be correct because the heart has only two ventricles. Indeed dissection disproves what they said [45].”

Furthermore, the first ever mention of coronary vessels is found on page 389 of Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun of Ibn al-Nafis translated as follows:

“His attribution of the nourishment of the heart to the blood in the right ventricle, can never be accepted as true because the nourishment of the heart is actually from the blood passing to it in the vessels situated in its substance [46].”

Another unmistakable description of the coronary vessels by Ibn al-Nafis, is also found on page 316 of the same book and is, hereby, translated for the first time:

“And here is a question that we ought to verify its answer. Someone could say: why is it that the vessel arising from the heart to the other organs gives at its beginning two branches; one of them circles round the heart and spread in its different parts and the other penetrate into the right ventricle? Whilst in the case of the liver, nothing separates from the vessel that arises from it, to the other organs, to spread in the different parts of the liver. The answer (to that question): the reason is that the vessel arising from the heart to the other organs serves to supply the vital spirit and life to the organs. It arises from the left ventricle of the heart, the place of the pneuma (vital animal spirit). Therefore if nothing separates off that vessel to supply the other parts of the heart, those parts will be devoid of the vital spirit and the power of life… [47]”

Moreover, in agreement with Iskander [48] and Ziedan [49], Ibn al-Nafis rejected the so called ebb and flow movement of the blood described by Galen and laid the seeds of the correct description of the systemic greater blood circulation. This is also clearly evident from statements by Ibn al-Nafis in his other books Risalat al-A’dha’ [50] and Al-Risalah al-Kamiliyah [51]. His findings in relation to the circulation and the coronary vessels together with his other anatomical and physiological discoveries, were accepted by scholars who came after him and were included in works such as Sharh Al-Qanun (Commentary on [Ibn Sina’s] ‘Canon’) by Sadid al-Din Muhammad Ibn Masoud al-Kazaruni, who completed his commentary in 745H/1344 and in Ali Ibn Abdallah Zayn al-Arab al-Misri’s Sharh al-qanun (completed in 751H/1350) [52]. Ibn al-Nafis description of the pulmonary circulation, together with other parts of his Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun, was also included as marginal notes added to the widely distributed copies of Ibn Sina’s Canon of Medicine and its commentaries [53].

Early in the 16th century, Andrea Alpagus (1450-1522), a professor of medicine in Padua University who spent 30 years in Syria studying Arabic medical manuscripts, translated into Latin, sections of Ibn al-Nafis Book Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun including his views on the pulmonary circulation [54]. This translation, printed in Venice in 1547, helped to spread Ibn al-Nafis’ description of pulmonary circulation to pre-modern European scholars and thus raise their doubts about Galen’s anatomy. Six years later, Ibn al-Nafis’ description of pulmonary circulation was accepted by Michel Servetus (1511-1553) who included it, verbatim, in his book Christianismi Restituto [55].

Then, in 1555, Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564), another professor of Padua University, described the pulmonary circulation in a manner similar to Ibn Nafis’ description, in the second edition of his famous book the De Fabrica Humani Corporis [56]. Another similar description was given by Juan Valvarde in 1554 and Realdus Columbus in 1559 in their books on anatomy [57] and in 1571 by Andrea Cesalpino (1519-1603) in his book Quaestionum Peripateticarum Libri Quinque, which documented further elaboration and experimentation including the first use of the word “circulation” [58]. Finally, William Harvey (1578-1657), who received his doctorate from Padua University in 1602, gave the full description of the blood circulation in his lectures in 1616, then in his famous book Exercitatio anatomica de motu cordis et sanguinis in animalibus printed in 1628 [59]. According to Jaleely [60], the description given for the coronary vessels in Harvey’s book is similar to that given by Ibn al-Nafis. It is also significant, in this evolutionary chain, that of these European medical scholars, three were fluent in the Arabic language: Alpagus, Servetus and Vesalius [61].

In his book Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun, Ibn al-Nafis, like previous Muslim scholars, emphasized ,that the doctor should have knowledge of anatomy in order to be able to identify the state of the organs and how they are related to each other. He allocated a special chapter entitled “on the benefits of studying the science of anatomy” and showed how essential this study is for reaching a diagnosis and for practicing medicine and performing different surgical, orthopaedic or ophthalmologic procedures [62]. Furthermore, in this book, he wrote a special chapter on the best mode for dissecting the following parts: bones, peripheral vessels and internal organs of the chest (heart, lung, big vessels and the diaphragm) [63].

Both Ibn al-Nafis in his book and Al-Razi (Rhazes) in his chapter on anatomy in his treatise Al-Mansuri, frequently mentioned the word Al-Musharrihun, which according to the etymology of the Arabic language is derived from the Arabic verb Yusharrih. According to Ibn Manzur’s lexicon Lisan al-‘Arab [64], this verb means dissecting the flesh and dissecting the flesh out of bones. Thus Musharrihun subsequently means the dissectors. Therefore, in contradiction to what Long [65] and many others state, the practice of dissection for medical teaching, was not prohibited in either the religion of Islam or the Islamic world. On the contrary, all the eminent Islamic physicians of that era stated that knowledge of anatomy leads to a deeper appreciation of God’s wisdom and omniscience [66].

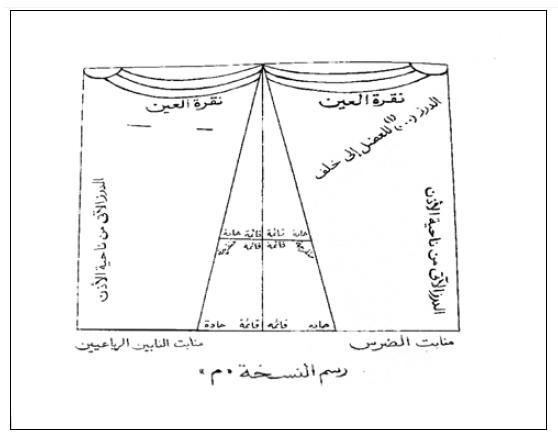

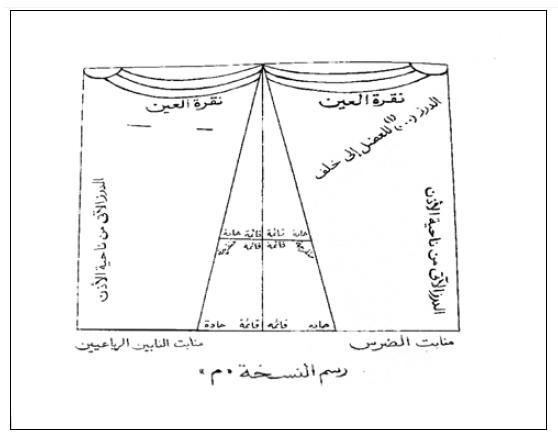

Furthermore, the presence of anatomical drawings within the text in Ibn al-Nafis’ Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun is a further step forward in illustrating medical text books; a trend that started and flourished in the Islamic period reflecting the role of direct observations and experience. This illustration of the maxillary sutures (Figures 3 and 4) in Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun is more sophisticated than the anatomical illustrations we have shown before in the Canon of Ibn Sina and the Mansuri book of Al-Razi and the Al-Mukhtar of Muhadhdhab al-Din al-Baghdadi [67].

Figure 3: Anatomical drawing of the maxillary sutures in one of the original manuscripts of Ibn al-Nafis’ book Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun. Source: Ibn al-Nafis, Kitab Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun (Cairo, 1988).

7. Contributions to the progress of urology

All the previously-mentioned contributions of Ibn al-Nafis helped in the establishment of the foundation of urology, as well as all other branches of medical and surgical subspecialties. However, of particular urological interest are the advances made by Ibn al-Nafis in uro-physiology. Contrary to Galen who described the bladder wall as formed of only one layer [68], Ibn al-Nafis, in his book Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun described the bladder wall as consisting of two layers [69]. Continuing with this original observation made by Al-Razi, Ibn Sina, Al-Zahrawi, and Al-Baghdadi, his description of the anti-reflux and micturition mechanisms were also contrary to Galen but conform well with our contemporary understanding [70].

Ibn al-Nafis’ full description of the vesico-ureteric anti-reflux mechanism is translated here:

“For this reason the base and back of the bladder is made of two layers and when the two canals known as ureters penetrate it, they first penetrate through the superior layer and continue for a distance then they penetrate the inferior layer opening into the bladder cavity. The benefit of that (arrangement) is that when the bladder is filled up and the inner layer presses upon the outer layer, the two canals (ureters) going in between the two layers will be compressed and thus occluded preventing the reflux of urine (retrogradely)… [71]”

In this description, Ibn al-Nafis differed from Al-Razi [72], Ibn Sina [73], Al-Zahrawi [74], and Al-Baghdadi [75] in specifying the base and back of the bladder as the regions where the bladder wall is made of two layers. This is another proof that he was not a copyist or a mere compiler and is further evidence of the scientific spirit that spread during the Islamic era and stimulated its scholars to rely on their own findings and describe their own observations.

With regard to urological practice, Ibn al-Nafis stressed as did all his predecessors in the Islamic era, the importance of clinical medicine. In the book Al-Mujaz, in addition to a general introductory chapter on physical signs, he started each of the chapters dealing with regional diseases by mentioning the specific related symptoms paying a lot of attention to differential diagnosis and prognosis. This illustrates Cumston’s description of the Arabian physicians as keen observers who excelled in diagnosis and prognosis with their description of symptoms showing a precision and an originality that could be only obtained by direct study of the disease [76].

Accordingly, in his book Al-Mujaz, Ibn al-Nafis distinguished between kidney stones and bladder stones with regard to their pathogenesis and clinical picture. He discussed how to differentiate renal from intestinal colic, bladder infections from kidney infections as well as the different types of inflammatory and non-inflammatory renal swellings [77]. In the conservative management of renal stones Ibn al-Nafis, advised diuresis only for short periods of time; not constantly as recommended by Ibn Sina [78]. In line with his general policy in Kitab al-Mujaz fi al-Tibb, Ibn al-Nafis listed only the commonly used and well known lithontriptic medicaments. Among those medicaments, he included a medicament which is not mentioned in Ibn Sina’s Canon of Medicine [79].

Figure 4: Anatomical drawing of the maxillary sutures in another original manuscript of Ibn al-Nafis’ book Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun. Source: Ibn al-Nafis, Kitab Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun (Cairo, 1988).

Both Ibn Sina and Ibn al-Nafis recommended the same dietary management for urinary stone patients. However, Ibn al-Nafis did not pay attention to the type of water intake whilst Ibn Sina advised avoidance of “turbid waters” [80]. This again proves the originality of Ibn al-Nafis and shows, in addition to many other pieces of evidence, that Al-Mujaz fi al-Tibb is not just a summary for the Canon of Medicine as claimed by some modern historians. He also disagreed with Hippocrate’s statement that penetrating wounds of the urinary bladder are always fatal [81]. Moreover unlike Paulus [82], Ibn al-Nafis did not recommend venesection in the management of patients presenting with stone impaction and acute pain [83]. As planned by Ibn al-Nafis, the book Al-Mujaz does not contain any details on operative treatment or surgical instrumentation. These are to be found in volume 42 of his encyclopedia Al-Shamil fi al-Sinaaa al-Tibbyaa [84], a manuscript of which is still waiting for editing and publication.

In conclusion, it is evident from this study that Ibn al-Nafis is the greatest physiologist of the Middle Ages and the main forerunner of Servetus, Vesalius, Columbus and Harvey in the description of pulmonary circulation as we know it today. He was also the first to describe the coronary vessels and the true concept of the blood supply of the heart. Moreover he described the presence of connecting passages in the substance of the lung between the branches of pulmonary artery and tributaries of pulmonary veins and pointed to the greater systemic circulation of blood from the heart to all organs and vice versa.

Ibn al-Nafis was also a talented physician and a gifted medical writer. His discoveries and medical works, greatly contributed to the progress of medical knowledge and the advancement of medical practice. His influence on the generations of doctors and scholars who came after him, both in the East and West, is well documented up to the seventeenth century.

8. Supplement: Commentary and Response

8.1. [Ibn] Al-Nafis and Servetus by Giles N. Cattermole

To the editor

I very much appreciated Abdel-Halim’s article about Ibn al-Nafis and his contribution to medicine and urology. Al-Nafis was certainly a great physiologist and physician, and is rightly credited with the discovery of the pulmonary circulation [85]. Michael Servetus (1511-1553) was the first writer in Christian Europe to describe the pulmonary circulation, although because Servetus was burned as a heretic along with his books, for many years it was Realdo Colombo (1516-1559) who was credited with the discovery. Both Al-Nafis and Servetus were neglected by Harvey when he applauded Colombo as his forerunner [86]. However, I would disagree with Abdel-Halim that Servetus included Al-Nafis’description of the pulmonary circulation “verbatim” in his book Christianismi Restitutio. The implication is that Servetus plagiarised Al-Nafis, whereas in fact, both men almost certainly described what they had found in their own anatomical investigations.

The idea that Servetus copied Al-Nafis derives from a comment by Haddad and Khairallah in 1936 [87], who noted the “striking parallelism” that both descriptions were published within a theological discourse, and also that they “made the same mistakes in practically the same phraseology.” It is highly unlikely that this is the case, partly as one wrote in Arabic, and the other in Latin. More importantly though, each described very different reasons for their understanding of the pulmonary circulation. Al-Nafis realized, contra Galen, that the interventricular septum was too thick to allow blood flow, and that instead the pulmonary artery must connect in the lungs with the pulmonary vein. Servetus observed the difference in color of blood in those vessels, and that the pulmonary artery was too large merely to provide nourishment for the lungs themselves [88].

In addition, although Al-Nafis did recognize that there were “perceptible connecting passages” between artery and vein, it was Servetus who first unequivocally described capillaries (in the lung and the choroid plexus), using that very word: “a new kind of vessels… hairlike [capillaribus] arteries… woven together very finely… the termination of arteries [89].” Nothing can detract from Al-Nafis’ position as the discoverer of the pulmonary circulation. However, for all his other faults, Servetus was not a plagiarist. He made the same discovery, independently although much later. And we should not detract from Servetus’ distinction as the first writer clearly to describe capillaries.

8.2. Reply from the Author Rabie E. Abdel-Halim

I would like to thank Dr. Giles Cattermole for his comment. I do agree with him on the distinguished status of Servetus in the history of medicine during the 16th century. Certainly, he was one of the greatest physicians of his time. In our paper [90], the review of the evolution of knowledge on pulmonary circulation was never meant to accuse him of plagiarism; a scholar of his calibre and character is never expected to plagiarize.

On pulmonary circulation and on capillaries, Servetus, in his great work Christianismi Restitutio (1553), presented what he accepted of the knowledge already available at his time. Early in the 16th century, Andrea Alpagus (1450?-1522), a professor of Medicine in Padua University who spent 30 years in Damascus studying Arabic Medical manuscripts, translated into Latin sections of Ibn al-Nafis’ Book Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun including his views on the pulmonary circulation. This translation, printed in Venice in the year 1547, helped to spread Ibn al-Nafis’ description of pulmonary circulation to European scholars and, thus, raise their doubts about Galen’s anatomy. According to Ullman, “Servetus’ presentation of the lung circulation resembled Ibn al-Nafis’ so strongly that one can hardly reject a direct influence” [91]. Ullman, in his comparative study quoted the text of both the Latin text of Servetus and the English translation of Ibn al-Nafis’ description. Many other authors came also to the same conclusion [92]. It is well documented that Servetus was an expert in the Arabic language [93] which he mastered during his university years in Toulouse [94].

References

[1] Castiglioni A. A History of Medicine. New York (NY): Jason Aronson, 1975, p. 278.

– Bu Malham A. “Introduction”. In: Bu Malham A, Attawi AN, Al-Sayyed F, Aser Al-Din M, Abdel-Satir A, editors, Ibn Katheer, Al-Bidayah wa’l-Nihayah, 3rd ed. Beirut; Dar Al-Kutub Al-Elmeyyah; 1978, pp. Aleph-Kaf.

– Muntasir A. Tarikh al-‘ilm wa-Dawr al-‘Ulmaa al-‘Arab fi Taqaddumihi. 8th ed. Cairo: Dar Al-Maarif, 1990, p. 177.

– Ziedan Y, Abdel-Qader M. “Introduction”. Ziedan Y, Abdel-Qader M, editors. Sharh Fusul Abuqrat. Beirut/Cairo: Al-Dar al-Mesreyya al-Lobnaneyyah, 1991, p. 42.

– Maarof BA. “Forward”. In: Al-Dhahaby MAO, Seyar A’lam al-Nobala’, Aranaouty S, editor. Riyadh: King Saud University, Muassasat al-Risalah, 1981, p. 12.

[2] Al-Dhahaby MAO. Tarikh al-Islam wa-Wafayat al-Mashahir wa-‘l-A’lam. In: Maarof BA, editor. Beirut: Dar Al-Gharb Al-Islami. 2003, pp. 597-598.

– Al-Dhahaby MAO. Al-‘Ibar fi Khabar man Ghabar, Zaglool BM, editor. Beirut: Dar Al-Kutub al-Ilmeyyah, 1985, p. 356.

– Al-Dhahaby MAO. Duwal al-Islam, Haydarabad. 2nd ed. Hyderabad (IN): The Osmania University Publications Bureau, 1365, p. 143.

[3] Al-Sobky, Tajul-Din. Tabaqat al-Shafi’yya al-Kobrah. Vol. 5. Beirut: Dar al-Maarifah, p. 129.

[4] Ibn Taghra Bardi, Shamsul-Deen MH. Al-Nujum al-Zahirah fi Muluk Misr wa-‘l-Qahirah. Dar Al-Kutub Al-Elmeyyah, 1992, vol 7: p. 318.

[5] Al-Maqrizi, AA. In: Att MA, editor. Al-Suluk Lima’rifat Duwal al-Muluk. Beirut: Manshorat Mohammad Ali Baidoon, 1997, vol. 2, p. 209.

[6] Al-Yafeie. Mir’at al-Janan wa-Ibrat al-Yaqzan fi Ma’arifat Hawadith al-Zaman. Al-Warraq Net Online Heritage Library, p. 721. Available here.

[7] Sarton G. Introduction to the History of Science. Carnegie Institution of Washington. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins Company; 1927-1931. Reprinted in New York: Robert E. Krieger, 1975, pp. 1099-1101.

[8] Ziedan Y, Abdel-Qader M. “Introduction”. In: Ziedan Y, Abdel-Qader M, editors. Ibn al-Nafis, Sharh Fusul Abuqrat. Beirut/Cairo, 1991, pp. 35-65.

[9] Ziedan Y. “Introduction”. In: Ziedan Y, editor. Ibn al-Nafis, Risalat al-A’dha’, Ma’a Dirasah Hawla Ibn al-Nafis wa-Manhajahu wa-Ibda’atuh. Cairo: Al-Dar al-Masreyyah Al-Libnaneyyah, 1991, pp 13-69.

– Ziedan Y., “Introduction”. In: Ibn al-Nafis, Al-Shamil fi al-Sina’a al-Tibbiyyah. Abu Dhabi: Al-Mojamma’ Al-Thaqafi, 2000, pp. 1-12. Al-Warraq Net Online Heritage Library. Available here.

[10] Ibn Al-Ghazzi, Diwan al-Islam, Al-Waraq Net Electronic Heritage Library, p. 91, Available here.

– Al-Soyoti, Husn al-Muhadarah fi Akhbar Misr wa-‘l-Qahirah, Al-Waraq. Net Electronic Heritage Library. p. 182. Available here.

– Ibn Al-Imad. Shadharat al-Dhahab fi Akhbar man Dhahab. Al-Arnaouti M, Al-Aranaouti Abdel-Qader, editors. Damascus and Beirut: Dar Ibn Katheer, 1991, pp. 701-702.

– Ibn Qadi Shohbah, Tabaqat Al-Shafi’iyah. Al-Waraq Net Electronic Heritage Library, page 107. Available here.

– Al-Babani, Ismaeil ibn Muhammad Ameen ibn Meer Saleem. Hadeyyat al-Arefin fi Asmaa al-Mu’allifin wa-Aathar al-Musannifin. Istanbul: Wikalat Al-Maarif Al-Jaleela fi Matbaatiha Al Baheyyah; 1951. 3rd ed. Reprinted in Tehran: Maktabat Al Islamiat Wa Al-Jaafari Tabreezi, 1387 H, p. 714.

– Al-Zarkaly, Khairul Deen, Al-A’lam: Qamus Tarajim Li-ashhar al-Rijal wa-‘l-Nisa’ Mina al-‘Arab wa al-Musta’ribin wa-‘l-Mustashriqin. 5th ed. Beirut: Dar Al-Elm Lilmalayeen; 1980, pp. 270-271.

– Van Deek E. Iktifa’ Al-Qanu’ bima huwa Matbu’ min Ashar Al-Ta’alif al-‘Arabiyah fi al-Matabi’ al-Sharqiyah wa-‘l-Gharbiyah. Edited by AMA Al-Bibillawy, Al-Fajjalah, Egypt: Al-Hilal Press, 1896, pp. 223-225. Al-Warraq Net Electronic Heritage Library, page 74 and 79. Available here.

– Al-Safadi KA. A’yan al-‘Asr wa-Awan al-Nasr. In: Abu Zaid A, Abu Amsha N, Maeid M, Salim M, editors. Publications of Jumaa Al-Majid Centre for Culture and Heritage. 1st ed. Damascus: Dar Al-Fikr and Beirut: Dar Al-Fikr Al-Mua’asir. 1998; Vol. 2: p. 404; Vol 4: pp. 222, 448.

– Al-Mohibby. Nafkhat Al-Rayhanah wa rashhat Tilaaa Al-Hanah, Al-Waraq Net Electronic Heritage Library. Available here.

– Essa A. “Ibn al-Nafis Biography”, in Mu’ajam al-Atibba’ min 650H hata yamnina hadha (1361H/1942): Dhayl ‘Uyun al-Anba’ fi-Tabaqat aI-Atiba’ Li-Ibn Abi Usaybia’a. 2nd ed. Beirut: Dar Al-Raeid Al-Arabi; 1982, pp. 292-296.

– Muntasir A. Tarikh Al-‘Ilm wa-Dawr al-‘Ulma’ al-‘Arab fi Taqaddumihi. 8th ed. Cairo: Dar Al-Maarif; 1990, pp. 133-135, 177-178.

– Abdel-Qader M. Muqaddimah fi Tarikh al-Tibb Al-‘Arabi. Beirut: Dar Al-Ulum al-Arabiyyah Lilltibaaa wa-‘l-Nashr; 1988, pp. 95-110.

– Omar AM, Hareedy AA, editors. “The Life and Era of Ibn al-Nafis and his Works”. In: Ibn al-Nafis, Al-Risalah al-Kamiiyyah fi a-Sirah a-Nabaweyyah. 2nd ed. Cairo: Islamic Heritage Revival Committee, Supreme Council for Islamic Affairs, Ministry of Endowments; 1978, pp. 23-72.

– Ghaliongy P, Shawqy J, Mounis H, Abu Rayyan MA, Al-Sayyad MM, Musa RS, editors. “Ibn al-Nafis Biography”, in Mawsu’at al-‘Ulum al-Islamiyyah wa-‘l-‘Uluma’ al-Muslimin. Beirut: Maktatabat Al-Maarif, pp. 175-176.

– Al-Ezbawy A. “Introduction”. In: Ibn al-Nafis, Al-Mujaz fi al-Tibb. Al-Ezbawy A, editor. 4th ed. Cairo: Islamic Heritage Revival Committee, Supreme Council for Islamic Affairs, Ministry of Endowments; 2004, pp. Sheen-25.

– Badran I. “Foreword”. In: Ibn al-Nafis, Al Mujaz Fi Al-Tibb. 4th ed. Cairo: Islamic Heritage Revival Committee, Supreme Council for Islamic Affairs, Ministry of Endowments; 2004, pp. Taa-Sin.

[11] Al-Yafeie. Mira’at al-Janan wa-‘Ibrat al-Yaqzan fi Ma’arifat Hawadith al-Zaman. Al-Warraq Net Online Heritage Library, p. 721. Available here.

– Ibn Al-Ghazzi, Shams Al-Din Abu Al-Maali Muhammad ibn Abdel-Rahman, Diwan al-Islam, Al-Waraq Net Electronic Heritage Library, p. 91, Available here.

– Al-Suyuti, Husn al-Muhadarah fi Akhbar Misr wa-‘l-Qahirah, Al-Waraq Net Electronic Heritage Library. p. 182. Available here.

– Ibn Qadi Shohbah, Tabaqat al-Shafeyyah, Al-Waraq Net Electronic Heritage Library, page 107. Available here.

– Al-Suyuti. Al-Itqan fi ‘Ulum al-Qur’an. Available here.

– Al-Suyuti. Al-Mizher. Al-Waraq Net Electronic Heritage Library. Available here.

– Ibn Masoom A. Sulafat Al-Asr Fi Mahasin Al-Shuaraa Bikul Misr. Available here.

– Ibn Masoom A. Anwâr al-Rabi’ fi Anwâ’ Al-Badi’. Available here.

– Al-Zibaidy M. Entry “Al-Wabaa“, in Taj Al-Aroos. Al-Warraq Net Electronic Heritage Library. Available here.

[12] Ibn al-Nafis. Al-Mujaz fi al-Tibb. Al-Ezbawy A, editor. 4th ed. Cairo: Islamic Heritage Revival Committee, Supreme Council for Islamic Affairs, Ministry of Endowments; 2004.

[13] Ibn al-Nafis. Kitab Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun. Qattaya S, editor. Cairo: The Supreme Council for Culture and the Egyptian Book Bureau; 1988.

[14] Ibn al-Nafis. Risalat al-A’dha’. Ziedan Y, editor. Cairo: Al-Dar Al-Masriyya al Lubnaneyyah; 1991.

[15] Ibn al-Nafis. Sharh Fusul Abuqrat. Ziedan Y, Abdel-Qadir M, editors. Cairo: Al Dar Al-Masreyya Al Lubnaneyyah; 1991.

[16] Ibn al-Nafis. Al-Mujaz Fi Al-Tibb. Al-Ezbawy A, editor. 4th ed. Cairo: Islamic Heritage Revival Committee, Supreme Council for Islamic Affairs, Ministry of Endowments; 2004.

[17] Cumston CG. “Islamic Medicine”. In: Cumston CG, editor. An introduction to the history of medicine from the time of the pharaohs to the end of the XVIII century. London (UK): Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner and Co. Ltd. New York: Alfred A. Knopf; 1926, p. 191.

[18] Leclerc L. Histoire de la médecine arabe. Paris: Ernest Ledaux; 1876, pp. 91-92.

[19] Al-Dhahaby MAO. Tarikh al-Islam wa-Wafayat al-Mashahir wa-‘l-A’lam. Maarof BA, editor. Beirut: Dar Al-Gharb Al-Islami; 2003, pp. 597-598.

– Al-Sobky, Tajul-Din. Tabaqat al-Shafi’iyaa al-Kobrah. Vol. 5. Beirut: Dar Al-Maarifah Lilltibaah Wa Al-Nashr Wa Al-Tawzeei, p. 129.

– Ibn Taghra Bardi, Shamsul-Deen MH. Al-Nujum al-Zahirah fi Muluk Misr wa –‘l-Qahirah. Vol. 7. Dar Al-Kutub Al-Elmeyyah; 1992, vol. 7: p. 318.

– Al-Suyuti, Husn al-Muhadarah fi Akhbar Misr wa-‘l-Qahirah, Al-Waraq Net Electronic Heritage Library. p. 182. Available here.

– Ibn Al-Imad. Shadharat al-Dhahab fi Akhbar Man Dhahab. Al-Arnaouti M, Al-Aranaouti Abdel-Qader, editors. Damascus and Beirut: Dar Ibn Katheer; 1991, pp. 701-702.

– Ibn Qadi Shohbah, Tabaqat Al-Shafi’iyah, Al-Waraq Net Electronic Heritage Library, page 107. Available here.

– Ibn Katheer. Al-Bidayah wa-‘l-Nihayah. Abu Malham A, Attawi A, Al-Sayyed F, Nasir Al-Din M, editors. 3rd ed. Beirut: Dar Al-Kutub Al-Ilmeyyah; 1978, p. 331.

[20] Hajji Khalifah MA. Kashf al-Zunun ‘An Asami al-Kutub wa-‘l-Funun. Yaltaqaya MS, Al-Klais RB, editors. 3rd ed. Tehran: Maktabat Al-Islamiyyah Wa Al-Jaafary Tabreezi; 1378H, p. 1024.

[21] Kahya E. “Ibn al-Nafis and his work Kitab Mujiz al-Qanon“. Studies in the history of medicine and science, vol. 9, 1985, pp. 89-94.

[22] Al-Babani, Ismaeil ibn Muhammad Ameen ibn Meer Saleem. Hadiyat al-‘Arifin fi Asma’ al-Moallifin wa-Athar al-Musannifin. Istanbul: Wikalat Al-Maarif Al-Jaleela fi Matbaatiha Al Baheyyah; 1951. 3rd ed. reprinted in Tehran: Maktabat Al Islamiat Wa Al-Jaafari Tabreezi; 1387 H, p. 714.

– Al-Zarkaly, Khairul Deen, Al-Aalam.. 5th ed. Beirut: Dar Al-Elm Lilmalayeen; 1980, pp. 270-271.

– Van Deek E. Iktifaa Al-Qanu’… Al-Bibillawy AMA (editor). Al-Fajjalah, Egypt: Al-Hilal Press; 1896, pp. 223-225. Online at Al-Warraq Net Electronic Heritage Library, page 74 and 79. Available here.

[23] Ibn al-Nafis. Al-Mujaz fi al-Tibb. Al-Ezbawy A, editor. 4th ed. Cairo: Islamic Heritage Revival Committee, Supreme Council for Islamic Affairs, Ministry of Endowments; 2004, p. 31.

[24] Iskander AZ. A Catalogue of Arabic Manuscripts on Medicine and Science in the Wellcome Historical Medical Library. London: The Wellcome Historical Medical Library Series; 1967, pp. 52-53.

[25] Ibn al-Nafis. Al-Shamil Fi Al-Sinaa Al-Tibbiyyah. Ziedan Y, editor. Abu Dhabi (UAE): Al-Mujammaa Al-Thaaqfi; 2000. Vol. 1 & 2.

[26] Al-Dhahaby MAO. Tarikh al-Islam… Maarof BA, editor. Beirut: Dar Al-Gharb Al-Islami; 2003, pp. 597-598.

[27] Ibn al-Nafis. Al-Shamil fi al-Sina’a al-Tibbiyyah. Ziedan Y, editor. Abu Dhabi: Al-Mujammaa al-Thaaqfi, 2000, 2 vols.

[28] Ziedan Y., “Introduction.” In: Ibn al-Nafis, Al-Shamil … Abu Dhabi: Al-Mojammaa Al-Thaqafi, 2000, pp. 1-12. Al-Warraq Net Online Heritage Library. Available here.

[29] Darweesh A. “Introduction”. In: Darweesh A, editor, Ibn Qadhi Shohbah A., Tarikh Ibn Qadhi Shuhbah al-Asadi al-Dimashqi. Damascus: The French Scientific Istitute for Arabic Studies, 1994, p. 11.

[30] Abdel-Halim RE. “Contributions of Ibn Zuhr (Avenzoar) to the Progress of Surgery: A Study and Translations from his book Al-Taisir“. Saudi Med J 2005; 26: pp. 1333-1339.

[31] Ibn al-Nafis. Al-Shamil… Ziedan Y, editor. Abu Dhabi: Al-Mujammaa Al-Thaaqfi, 2000, 2 vols.

[32] Ibn al-Nafis. Al-Mujaz … Al-Ezbawy A, editor. 4th ed. Cairo: Islamic Heritage Revival Committee, Supreme Council for Islamic Affairs, Ministry of Endowments, 2004.

[33] Iskander AZ. “The Comprehensive Book on the Art of Medicine by Ibn al-Nafis”. The second International Islamic Medicine Conference (Kuwait, 1982). Available here.

[34] Ibn al-Nafis. Risalat Al-A’dha’. Ziedan Y, editor. Cairo: Al Dar Al-Masreyya Al Lubnaneyyah, 1991.

[35] Ibn al-Nafis. Kitab Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun. Qattaya S, editor. Cairo: The Supreme Council for Culture and the Egyptian Book Bureau, 1988.

[36] Ibn al-Nafis. Al-Mujaz… Cairo: Islamic Heritage Revival Committee, Supreme Council for Islamic Affairs, Ministry of Endowments, 2004, 4th ed.

[37] Ibn al-Nafis. Al-Muhadhdhab fi al-Kuhl al-Mujarrab. Wafai MZ, Qalaji MR, editors. 2nd ed. Riyadh: Safir Press, 1994.

[38] Ibn al-Nafis. Sharh Fusul Abuqrat. Ziedan Y, Abdel-Qadir M, editors. Cairo: Al Dar Al-Masreyya Al Lubnaneyyah, 1991, pp. 93-94.

[39] Ibn al-Nafis. Kitab Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun. Qattaya S, editor. Cairo: The Supreme Council for Culture and the Egyptian Book Bureau, 1988, p. 17.

[40] Ibn al-Nafis. Sharh Tashreeh al-Qanun. Cairo, 1988, pp. 293-294.

[41] Poynter FNL. “Foreword”, in: Iskandar AZ, editor. A Catalogue of Arabic Manuscripts on Medicine and Science in the Wellcome Historical Medical Library. London: The Wellcome Historical Medical Library Series, 1967, pp. v-viii.

[42] Iskander AZ. “Introduction”, in: Iskander AZ, editor. A Catalogue of Arabic Manuscripts… London, 1967, pp. 38-42.

[43] Castiglioni A. A History of Medicine. Edited by EB Krumbhaar. Translated from the Italian. New York (NY): Jason Aronson, 1975, pp. 278-279.

[44] Ducasse E, Speziale F, Basle J C, Midy D. “Vascular Knowledge in Medieval Times was the Turning Point for Humanistic Trend”, Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2006, 31: 600-608.

– Al-Dabbagh SA. “Ibn al-Nafis and the Pulmonary Circulation”, Lancet 1987, 1: 1148.

– Khan IA, Daya SK, Gowda RM. “Evolution of the Theory of Circulation”. Int J Cardiol 2005, 98: 519-521.

– Abdul-Aziz L A S. “Does history repeat itself in medicine?” Postgrad Med J 2001; 77: 743.

– Nagamia HF. “A biographical sketch of the discoverer of the pulmonary and coronary circulation”, JISHIM, 2003, 1: 22-28. Available here.

– Portraits des Médecins. Ibn al-Nafis connu sous le nom Ala-al-Din Abu al-Hasan Ali Ibn Abi al-Hazm al-Qarshi al-Damashqi al-Misri, 1213-1288 , médecin et anatomiste arabe. Available here.

– Bylebyl JJ, Pagel W. “The chequered career of Galen’s doctrine on the pulmonary veins”. Med His 1971; 15: 211-229.

– Cattermole GN. “Michael Servetus: physician, Socinian and victim”. J R Soc Med 1997; 90: 640-644.

– Meade RH. “The evolution of our knowledge of anatomy”. In: Meade RH, editor. An introduction to the history of surgery. Philadelphia (PA): London (UK), Toronto; WB Saunders Company; 1968, p 5.

[45] Ibn al-Nafis. Kitab Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun. Qattaya S. editor. Cairo: The Supreme Council for Culture and the Egyptian Book Bureau, 1988, p. 388.

[46] Ibn al-Nafis. Kitab Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun. Cairo, 1988, p. 389.

[47] Ibn al-Nafis. Kitab Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun. Cairo, 1988, p. 316.

[48] Iskander AZ. “Introduction”. In: Iskander AZ, editor. A Catalogue of Arabic Manuscripts… London, 1967, p. 40.

[49] Ziedan Y. “Introduction”. Ibn al-Nafis, Risalat Al-A’dha’… Cairo/Beirut, 1991, pp. 63-66.

[50] Ziedan Y. “Introduction”. Ibn al-Nafis, Risalat Al-A’dha’… Cairo/Beirut, 1991, pp. 63-66.

[51] Ziedan Y. “Introduction”. Ibn al-Nafis, Risalat Al-A’dha’… Cairo/Beirut, 1991, pp. 63-66.

– Ibn al-Nafis. Al-Risalah Al-Kamiliyah fi al-Sirah al-Nabawiyah. Omar MA, Hareedy AA, editors. 2nd ed. Cairo: Islamic Heritage Revival Committee, Supreme Council for Islamic Affairs, Ministry of Endowments, 1978, pp. 155-156.

[52] Iskander AZ. “The Comprehensive book on the Art of Medicine by Ibn al-Nafis”. The second International Islamic Medicine Conference (Kuwait, 1982). Available here.

– Iskander AZ. “Introduction”. A Catalogue of Arabic Manuscripts… London, 1967, p. 50.

– Soubani AO, Khan FA. “The discovery of the pulmonary circulation revisited”. Ann Saudi Med 1995, 15:185-186.

– Jaleely M, Ta’thir al-tibb al-Arabi fi al-tibb al-Ururubbi fi al-qurun al-wusta. Reprint from Part III and Part IV, Vol 32. Baghdad: Mijalat Al-Majmaa Al-Elmy Al-Iraqi; 1981, pp. 186-210.

– Ghalioungui P. “Was Ibn al-Nafis unknown to the scholars of the European Renaissance?” Clio Med 1983; 18: 37-42.

[53] Iskander AZ. “The Comprehensive book on the art of medicine by Ibn al-Nafis”. The second International Islamic Medicine Conference (Kuwait, 1982). Available here.

– Soubani AO, Khan FA. “The discovery of the pulmonary circulation revisited”. Ann Saudi Med 1995, 15:185-186.

– Jaleely M, Ta’thir al-tibb al-Arabi … Baghdad, 1981, pp. 186-210.

– Ghalioungui P. “Was Ibn al-Nafis unknown to the scholars of the European Renaissance?” Clio Med 1983; 18: 37-42.

[54] Omar AM, Hareedy AA, editors. “The life and era of Ibn al-Nafis and his works”. In: Ibn al-Nafis, Al-Risalah al-Kamiliyyah… Cairo, 1978, pp. 23-72.

– Iskander AZ. “The Comprehensive book on the art of medicine by Ibn al-Nafis”. The second International Islamic Medicine Conference (Kuwait, 1982). Available here.

– Nagamia HF. “A biographical sketch of the discoverer of the pulmonary and coronary circulation”, JISHIM, 2003, 1: 22-28. Available here.

– Iskander AZ. “Introduction”. A Catalogue of Arabic Manuscripts… London, 1967, p. 50.

– Soubani AO, Khan FA. “The discovery of the pulmonary circulation revisited”. Ann Saudi Med 1995, 15:185-186.

– Jaleely M, Ta’thir al-tibb al-Arabi… Baghdad, 1981, pp. 186-210

[55] Omar AM, Hareedy AA, editors. “The life and era of Ibn al-Nafis and his works”. In: Ibn al-Nafis, Al-Risalah Al-Kamiliyyah… Cairo, 1978, pp. 23-72.

– Iskander AZ. “The Comprehensive book on the art of medicine by Ibn al-Nafis”. The second International Islamic Medicine Conference (Kuwait, 1982). Available here.

– Nagamia HF. “A biographical sketch of the discoverer of the pulmonary and coronary circulation”. JISHIM, 2003, 1: 22-28. Available here.

– Soubani AO, Khan FA. “The discovery of the pulmonary circulation revisited”. Ann Saudi Med 1995, 15:185-186.

– Jaleely M, Ta’thir al-tibb al-Arabi… Baghdad, 1981, pp. 186-210.

– Ghalioungui P. “Was Ibn al-Nafis unknown to the scholars of the European Renaissance?” Clio Med 1983; 18: 37-42.

[56] Soubani AO, Khan FA. “The discovery of the pulmonary circulation revisited”. Ann Saudi Med 1995, 15:185-186.

– Jaleely M, Ta’thir al-tibb al-Arabi… Baghdad, 1981; pp. 186-210.

– Ghalioungui P. “Was Ibn al-Nafis unknown to the scholars of the European Renaissance?” Clio Med 1983; 18: 37-42.

[57] Omar AM, Hareedy AA, editors. “The life and era of Ibn al-Nafis and his works”. In: Ibn al-Nafis, Al-Risalah al-Kamiliyyah… Cairo,1978, pp. 23-72.

– Nagamia HF. “A biographical sketch of the discoverer of the pulmonary and coronary circulation”. JISHIM, 2003, 1: 22-28. Available here.

– Soubani AO, Khan FA. “The discovery of the pulmonary circulation revisited”. Ann Saudi Med 1995, 15:185-186.

– Jaleely M, Ta’thir al-tibb al-Arabi … Baghdad, 1981, pp. 186-210.

– Ghalioungui P. “Was Ibn al-Nafis unknown to the scholars of the European Renaissance?” Clio Med 1983; 18: 37-42.

[58] Ghalioungui P. “Was Ibn al-Nafis unknown to the scholars of the European Renaissance?” Clio Med 1983; 18: 37-42.

– Lilly Library (Indiana University, Bloomington). Medicine: an exhibition of books relating to medicine and surgery from the collection formed by J.K. Lilly. An Exhibition: a machine-readable transcription. Available here.

[59] Omar AM, Hareedy AA, editors. “The life and era of Ibn al-Nafis and his works”. In: Ibn al-Nafis, Al-Risalah Al-Kamiliyyah… Cairo, 1978, pp. 23-72.

– Nagamia HF. “A biographical sketch of the discoverer of the pulmonary and coronary circulation”. JISHIM, 2003, 1: 22-28. Available here.

– Soubani AO, Khan FA. “The discovery of the pulmonary circulation revisited”. Ann Saudi Med 1995, 15:185-186.

– Jaleely M, Ta’thir al-tibb al-Arabi… Baghdad, 1981, pp. 186-210.

– Ghalioungui P. “Was Ibn al-Nafis unknown to the scholars of the European Renaissance?” Clio Med 1983; 18: 37-42.

[60] Jaleely M, Ta’thir al-tibb al-Arabi… Baghdad, 1981, pp. 186-210.

[61] Jaleely M, Ta’thir al-tibb al-Arabi… Baghdad, 1981, pp. 186-210.

[62] Ibn al-Nafis, Kitab Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun. Qattaya S, editor. Cairo: The Supreme Council for Culture and the Egyptian Book Bureau; 1988, pp. 21-24.

[63] Ibn al-Nafis, Kitab Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun. Qattaya S, editor. Cairo: The Supreme Council for Culture and the Egyptian Book Bureau; 1988, p. 30.

[64] Ibn Manzur. Lisan Al-Arab. Alkabeer AA, Hasballah MS, Al- Shathly HM, editors. Vol. 4. Cairo: Dar Al-Maarif, pp. 2228.

[65] Long ER. A History of Pathology. New York: Dover Publications, Inc; 1965, pp. 22-27.

[66] Abdel-Halim RE, Abdel-Maguid TE. “The functional anatomy of the uretero-vesical junction. A historical review”. Saudi Med J 2003; 24: 815-819.

– Abdel-Halim RE. “Contributions of Ibn Zuhr (Avenzoar) to the progress of surgery: a study and translations from his book Al-Taisir”. Saudi Med J 2005; 26: 1333-1339.

– Abdel-Halim RE. “Contributions of Muhadhdhab Al-Deen Al-Baghdadi to the progress of medicine and urology. A study and translations from his book Al-Mukhtar.” Saudi Med J 2006; 27: pp. 1631-1641.

[67] Abdel-Halim RE. “Contributions of Muhadhdhab Al-Deen Al-Baghdadi to the progress of medicine and urology…” Saudi Med J 2006; 27: pp. 1631-1641.

[68] May MT. Translator. Galen on the uses of different parts of the body. Vol. II. Ithaca (NY): Cornell University Press; 1968, pp. 269 & 275.

– Singer C. Galen on anatomical procedures. De Anatomicis Administrationibus. In: Cumberlege G, editor. A Wellcome Historical Medical Museum Publication. Book VI. London (UK), New York (NY), Toronto (CA): Oxford University Press; 1956, p. 168.

[69] Ibn al-Nafis. Kitab Sharh Tashrih Al-Qanun. Cairo, 1988, pp. 431-432.

[70] Abdel-Halim RE, Abdel-Maguid TE. “The functional anatomy of the uretero-vesical junction. A historical review”. Saudi Med J 2003; 24: 815-819.

[71] Ibn al-Nafis. Kitab Sharh Tashrih Al-Qanun. Cairo, 1988, pp. 431-432.

[72] De Koning P. Trois Traites D’Anatomie Arabes Par Muhammad Ibn Zakariyya Al-Razi, Ali Ibn Al-Abbas et Ali Ibn Sina, Texte Inédit de deux Traités, Traduction de P. De Koning, Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1903; reissued in 1986 by Institut Fur Geschichte der Arabisch-Islamischen Wissenschaften an der Johann Wolfgang-Goethe Universitat, Frankfurt am Main, pp. 72, 82.

– Al-Razi (Rhazes). Kitab Al-Hawi fi al-Tibb. 1st ed. Vol. 10. Hyderabad (IN): Dairatul Maarif Al-Osmania; 1961, pp. 154-156.

[73] Ibn Sina. Kitab Al-Qanun fi al-Tibb. Cairo: Boulaq Ameereyyah Press; 1877, vol. 2, p. 507.

[74] Alzahrawi (Albucasis). Kitab Aa-Tasrif, Manuscripts No. 4009 and 4932. Dublin: The Chester Beatty Library.

[75] Al-Baghdadi Muhadhdhabul-Din. Al-Mukhtarat fi al-Tibb. Vol. 1. Hyderabad: Osmania Oriental Publication Bureau; 1940, p. 60.

[76] Cumston CG. “Islamic Medicine”. In: Cumston CG, editor. An introduction to the history of medicine from the time of the pharaohs to the end of the XVIII century. London (UK): Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner and Co. Ltd. New York: Alfred A. Knopf; 1926, p. 192.

[77] Ibn al-Nafis. Al-Mujaz fi al-Tibb. Al-Ezbawy A, editor. 4th ed. Cairo: Islamic Heritage Revival Committee, Supreme Council for Islamic Affairs, Ministry of Endowments; 2004, pp. 239-241.

[78] Ibn al-Nafis. Al-Mujaz fi al-Tibb. Cairo, 2004, pp. 239-241.

[79] Ibn al-Nafis. Al-Mujaz fi al-Tibb. Cairo, 2004, pp. 239-241.

– Ibn Sina, Al-Qanun fi al-Tibb. Vol. II. Cairo: Boulaq Ameereyyah Press; 1877, pp. 501-504.

[80] Ibn al-Nafis. Al-Mujaz fi al-Tibb. Cairo, 2004, pp. 239-241.

– Ibn Sina, Al-Qanun fi al-Tibb Cairo: Boulaq, 1877, vol. 2, pp. 501-504.

[81] Ibn al-Nafis, Sharh Fusul Abuqrat. Ziedan Y, Abdel-Qadir M, editors. Cairo: Al Dar Al-Masreyya Al Lubnaneyyah; 1991, pp. 436-439.

[82] Paul of Aegina. The Seven Books of Paulus of Aeginata. Translated from the Greek with a commentary. Vol. 3. London: Sydenham Society; 1844-47, pp. 541-543.

[83] Ibn al-Nafis. Al-Mujaz fi al-Tibb. Cairo, 2004, pp. 239-241.

[84] Iskander AZ. “The Comprehensive book on the art of medicine by Ibn al-Nafis”. The second International Islamic Medicine Conference (Kuwait, 1982). Available here.

[85] In the original publication, this footnote refers to the article by Professor Abdel-Halim: “Contributions of Ibn al-Nafis (1210-1288 AD) to the progress of medicine and urology” republished here (added by the editor).

[86] Cattermole GN. “Michael Servetus: physician, Socinian and victim.” J R Soc Med 1997; 90: 640-644.

[87] Haddad SI, Khairallah AA. “A forgotten chapter in the history of the circulation of the blood. Ann Surg 1936; 104: 1-8.

[88] Cattermole GN. “Michael Servetus: physician, Socinian and victim”; op. cit.

[89] O’Malley CD. Michael Servetus – a translation of his non-theological writings. Philadelphia (PA): American Philosophical Society, 1953.

[90] In the original publication, this footnote refers to the article by Professor Abdel-Halim: “Contributions of Ibn al-Nafis (1210-1288[CE]) to the progress of medicine and urology” republished here (added by the editor).

[91] Ullman M, Islamic Medicine. Islamic Surveys, Vol. 11, Edinburgh (IR): Edinburgh University Press, 1978, pp. 68-69.

[92] In the original publication, this footnote refers to the article by Professor Abdel-Halim: “Contributions of Ibn al-Nafis (1210-1288[CE]) to the progress of medicine and urology” republished here (added by the editor).

[93] Gier N, The 454th anniversary of burning of Michael Servetus. Online here.

[94] Goldstone L, Goldstone N. Out of the flames: The remarkable story of a fearless scholar, a fatal heresy, and one of the rarest books in the world. New York: Broadway Books; 2003. p. 56.

– Dibb AMT. Servetus, Swedenborg and the nature of God. University Press of America; 2005, p. 123. Read online (Google books).

*Formerly Professor of Urology, King Saud University College of Medicine and King Khalid University Hospital, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Professor Rabie E. Abdel-Halim is a member of Muslim Heritage Awareness Group (MHAG), a consulting network working with FSTC.

4.7 / 5. Votes 195

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

Muslim Heritage:

Send us your e-mail address to be informed about our work.

This Website MuslimHeritage.com is owned by FSTC Ltd and managed by the Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilisation, UK (FSTCUK), a British charity number 1158509.

© Copyright FSTC Ltd 2002-2020. All Rights Reserved.